bookshelf |

November/December 2002 |

|||

Hungry for freedom in times of social changeby Rosemary Bray McNatt

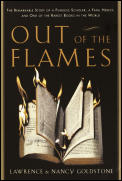

"The early sixteenth century was the crossroads where the medieval world, the Renaissance, the Inquisition, the New World, and the modern world all met," the authors write, and they make a good case in this fascinating book. They begin not with Servetus himself but with a brief history of the printed word, describing Johann Gutenberg (apparently a cranky and disagreeable sort) and Johann Fust, a Mainz-based financier who advanced money to the father of the printing press, then waited until Gutenberg had finished printing a new Bible before foreclosing on the loans and taking over his business. The entire book meanders this way, often breaking up Servetus's story with illuminating (and sometimes distracting) asides. The son of a Spanish noble family, Michael Servetus was born Miguel Serveto Conesa in 1511. Brilliant, well educated, and socially inept, he was, by age thirteen, fluent in several languages including Hebrew. "In most of Christian Europe, Hebrew was a forbidden language," the authors report. "It was considered dangerous, mystical, and subversive. The Church was adamantly against it: Knowledge of Hebrew meant that the Old Testament could be read in its original form without resorting to approved translations. . . . Because of Servetus's views on the Trinity, his enemies would later hypothesize that he was himself a Jew, but there is nothing to indicate that this was so." At thirteen, he was sent by his father to the university in Zaragossa, where he was mentored by Juan de Quintana, a Humanist admirer of Erasmus. It was Quintana who exposed the young Serveto to the then-revolutionary writings of Martin Luther. By the age of sixteen, he was a student at the University of Toulouse, joining with other subversive students in reading the Bible secretly — an act that was then punishable by imprisonment or death. He learned to read Arabic and began to read the Qur'an as well. It was during this period of immersion in sacred texts that Serveto (who changed his name to the Latin Servetus as an act of homage to the growing Humanist movement) began to form the heretical ideas that would lead to his death. By 1531, Servetus had moved to Strasbourg, where he completed work on his first book, De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). According to the Goldstones, "As even Servetus later acknowledged, the writing itself was often crude and rushed, betraying both the author's youth and his sense of urgency. . . . Still, even his fiercest detractors acknowledged that Errors of the Trinity was a prodigious piece of scholarship." Nonetheless, heresy was heresy, and Servetus fled Strasbourg. But Servetus was both passionate and intemperate. He began work on a second anti-Trinitarian manuscript, The Restitution of Christianity: In the body of the work, all the old themes were there: the injustice of infant baptism, the contortions of the Scriptures, the myth that was the Trinity, but most of all, the assertion that God existed in all people and things. . . . The book was to be published anonymously, but the manuscript contained several laughably obvious clues. . . . Opting for maximum provocation over discretion, Servetus included, right up front, the text of the thirty letters that he had written to Calvin. It was, in fact, this taunting and acrimonious correspondence with the arrogant and humorless John Calvin that led finally to Servetus's capture and execution in 1553 — and to the destruction of all but three copies of his book. The final third of the Goldstones' book is devoted to the search for the manuscript of Servetus's last work, a romp through Enlightenment Europe and nineteenth-century America. Alert readers who can track the book's many compelling digressions will find in Out of the Flames a fresh look at one of our religious movement's essential stories as well as a reminder that our free faith was purchased at tremendous cost. Until the 1960s, the story of African Americans in the Unitarian and Universalist movements had been, with few exceptions, a dim tale of condescension, scorn, and betrayal. Pioneering African-American men and women drawn to preach liberal religion as ministers fared especially poorly; white male leaders of the movement seemed constitutionally unable to imagine that people of African descent might cherish freedom of belief as much as they. In spite of that tragic misperception, there have always been people of color who have found inspiration in the principles of liberal religion.

In The New Woman of Color: The Collected Writings of Fannie Barrier Williams, 1893-1918, readers will be introduced not only to Williams, through her speeches and correspondence, but to her complex era. Williams's life straddled the heady days of Reconstruction, when newly freed black people achieved the barest glimpse of liberty, and the institution of legal segregation, when whites rebelled against the specter of social equality with blacks and stifled progress for generations. A superb introductory essay by Deegan grounds the reader in the milieu of the Progressive Era. "Like many other educated young women from the northeast, Williams was well read in the transcendentalists, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and the radical pacifist Henry David Thoreau. Although her family was Baptist, she became a Unitarian and was highly critical of Christianity." But her independent thinking was combined with a powerful commitment to her people. "Upon graduation . . .Williams made an unusual choice for an African American woman when she joined other northeastern 'school marms' to train the young, newly emancipated children of the South. Her unique role in comparison to that of the white women who went south arose from the fact that she was not going to 'help the helpless,' but to represent her own community and to find herself in their shared fate." Deegan helps readers connect Williams not only to influential black intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, but to Hull House founder Jane Addams and the influential Unitarian Celia Parker Wooley, with whom Williams enjoyed a lifelong friendship. Williams spoke at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where her mere presence created controversy among both blacks and whites. She also worked with black and white women to found the Frederick Douglass Center, a settlement house on Chicago's South Side modeled after Hull House. Committed to a life of biracial egalitarianism at a time when black activists felt it necessary to choose sides, Williams was often misunderstood as an apologist for whites unwilling to share social power with black citizens. Her membership with Celia Parker Wooley in both the Chicago Women's Club (after a protracted battle) and at Chicago's All Souls Unitarian Church placed her in milieus to which most black people had no access. Yet her work on behalf of black Chicagoans was tireless, including her participation in both the NAACP and the National Urban League during their founding periods and her leadership in the black women's club movement, a major avenue of social uplift for blacks moving to urban areas from the Southern states. "I dare not cease to hope and aspire and believe in human love and justice, but progress is painful and my faith is often strained to the breaking point," she wrote in a brief autobiographical sketch. Williams' passionate voice calls to us from across a century and asks us to examine ourselves, our liberal faith, and the future we hope to create. The Rev. Rosemary Bray McNatt is a contributing editor for UU World and minister of the Fourth Universalist Society in New York City.

| ||||

Copyright © 2002 Unitarian Universalist Association | Privacy Policy | Contact Us | Search Our Site | Site Map

Last updated November 21, 2002. Visited times since November 6, 2002.