| November/December 2002 |

||

|

| ||

We set out in a dilapidated Toyota Hilux pickup that Mohammed's men had captured from the Taliban at nearby Tora Bora. As the Toyota bounced over narrow lanes through mud-walled villages and past poppy fields with blazing red blossoms, Mohammed tried to explain what had happened at Mudoh. He said the Americans had relied on bad information from local fighters they had given cash and satellite phones in exchange for on-the-ground intelligence. These fighters had been quarrelling with residents of Mudoh, Mohammed told me, and out of revenge they had falsely told the Americans that the village was a Taliban and Qaeda command post. The Americans did not verify the information with him or other senior commanders, Mohammed said, even though he spoke almost daily with his Special Forces contacts.

"And so this village was destroyed." Mohammed spoke in a flat tone, without rancor or regret. Whatever happened, good or bad, was meant to happen — even the misdirected U.S. air strike that accidentally killed four of his own soldiers the same week Mudoh was flattened. The deaths of so many civilians was a terrible thing, especially on his watch, he said. But he shrugged and murmured: "It is Allah's will."

The dirt path ended at a mountain stream. Across several rocky ridges lay the spectral remains of Mudoh. Mohammed posted two of his men at the top of the first ridge and the rest of us continued on foot to the village. The two sentries would cover any attack from our rear. "This is a dangerous place," Mohammed explained. The Taliban was gone, but not Taliban sympathizers.

An hour's walk over rocky terrain brought us to Mudoh, where Mohammed was greeted perfunctorily by the village headman, Janat Khan, a stout man in a grey pakool, the flat wool cap favored by Pashtun tribesmen. But when I was introduced as an American, the mayor was not able to quiet the crowd of villagers who had suddenly emerged from the ruins of their homes, shouting and gesturing. Mohammed's militiamen tensed and gripped their Kalashnikovs.

Piara Gul, a villager with fierce green eyes, grabbed the hand of my Afghan translator, Omar Nassih. He began bending and twisting Omar's fingers, ticking off the indignities inflicted on his village by the Americans. This rough hand play, Omar explained later, was an Afghan expression of anger, a challenge to a fight. Omar nodded calmly as Gul rattled off the names of his wife, mother, and seven children, all killed in their sleep. He was shouting their names, weeping in anger and sorrow. The rest of the villagers took up his cries, hectoring Omar, but Omar quieted them by embracing Gul and assuring the villagers that we had come to tell their story. Gul released his tight grip on Omar's fingers.

The rest of the survivors surrounded me, vividly describing the U.S. attack, which had come as the village slept one cold night in November. They spoke of women screaming and children wailing, the cows and the sheep blown from their pens, the mud-and-timber dwellings in flames, the grain bins burned, the tiny hilltop mosque crushed and smoking. The crime was compounded by the fact that it came during the holy month of Ramadan. The villagers had been sleeping the deep peaceful sleep of the faithful after a late-night Ramadan feast.

The villagers insisted on showing me the ruins of their homes and the rows of graves in the hillside cemetery. They displayed the stones and timbers they had salvaged from the wreckage in the hope that someday Mudoh would be rebuilt. Some of the men — all the women were confined to their wrecked homes and out of sight of visitors, in the Afghan custom — began to weep and wail at the gravesites. Muttering and curses rose above the loud flapping of the graveside mourning flags. Gul glared at us, his hands trembling. Mohammed seemed alarmed. "We must leave — now!" he said suddenly.

We thanked the headman and moved quickly down the stone path from the village. We jogged at a fast clip until the ruined village was a dark spot on the ridgeline. At last our gunmen stopped and kneeled in the dirt, smeared with sweat, their hands still gripping their weapons. Mohammed idly slapped their backs, raising clouds of brown dust from their fatigues. Omar leaned over and whispered to me: "Those villagers — they wanted to stone us to death."

I spent more than three months traveling across Afghanistan, but my visit to Mudoh was the only time I felt directly threatened. The experience underscored for me just how close to the surface violence simmers in a country where most adult men have weapons and entire provinces are ruled by warlords and their militias, a country where death can come at any moment, from the air or from other Afghans — including Afghans who will lie to U.S. forces to get their rivals bombed. It also reinforced the underlying resentment and suspicions that Afghans hold for outsiders, even the American soldiers whom they greeted as liberators after Operation Enduring Freedom toppled the Taliban. As a Unitarian Universalist, I found my values and beliefs tested in a nation where tolerance is an unknown concept, democracy is a distant rumor, and women are treated as chattel.

Visiting Afghanistan is like returning to a pre-industrial age. Outside the cities, the countryside looks like landscapes painted in the eighteenth century. Plows are pulled by oxen. Families travel by donkey cart. Peasants live in crude houses made of mud, straw, and clay. Landowners live in adobe fortresses with high walls cut with square openings for gun placements. Subsistence farmers cook and heat with wood, coal, or dung. Paved roads end a few miles outside the cities, degenerating into mudholes in the winter and dusty tracks in the summer. Electricity is spotty, even in cities. Phone lines are largely nonexistent, cell phones don't work, and the only way to call someone in another town is via satellite phones that only the well-to-do can afford.

It is difficult to apply Unitarian Universalist values in such a place. Millions of Afghans wake up each day wondering whether they will find food, clean water, a place of shelter — and whether they or someone they love will be shot, stabbed, or robbed, or killed by a land mine, rocket attack, or air raid. More than six million people out of a total population of twenty-three million rely on international food aid. Many Afghans have been left homeless by war, but many more are victims of a four-year drought that has devastated villages where subsistence farming and livestock herding normally sustain families. At one point, the vast Maslakh displaced persons camp in the high desert of western Afghanistan was the largest such camp in the world. As many as 270,000 people lived in tents or mud huts, totally dependent on relief agencies for food, heat, and clean water.

When I visited the camp, its worn paths were smeared with human waste and children ran barefoot in subfreezing temperatures. Buffeted by stinging winter winds, boys and girls lined up twice a day by the thousands to wait for bowls of high-protein porridge. Some of the girls made dolls from rags stuffed with dried weeds, and the boys carved toy assault rifles from planks of wood. I wanted to hand out money to every wretched child and mother I saw, but camp rules prohibited it. Even the existence of the camp itself posed a moral dilemma for relief officials. They worried that Maslakh, as crude as it was, had created a culture of dependency among Afghans by luring them from their villages, livestock, and crops. Because the camp was attracting people who could still survive in their villages but simply sought free food and supplies, officials were planning to shut down the camp. "How do you make a safe, clean camp without attracting people from all over?" asked Alejandro Chicheri of the World Food Program. "That's our Catch-22."

I felt helpless; how does one person make a difference in a country beset by such infinite human suffering? Simple charity isn't enough, for humanitarian organizations are already raising and spending millions of dollars. Imposing Western values of democracy and human rights is a long-term and ultimately frustrating endeavor in a nation with a tribal and patriarchal culture. Little will improve without immediate basic security, but U.S. troops cannot stay forever and the security provided by international peacekeeping forces extends no further than Kabul. For Unitarian Universalists living in relative comfort and privilege in the U.S., Afghanistan can seem remote, alien, and impenetrable. The urge to "do something" is undeniable. The means and methods are less evident.

Like many Third World nations, Afghanistan is a creation of colonial interests and rivalries. Even after eighty-three years as an independent nation, it remains a collection of tribes. The current, U.S.-backed government in Kabul controls only the capital. The rest of the country is run by warlords who rule vast ethnic fiefs, levying taxes and fielding powerful private armies. Afghanistan's borders were set by the British, who invaded in the nineteenth century. Afghans have suffered through centuries of invasion and conquest, from Alexander the Great to Arab armies to Genghis Khan to Tamerlane to the Soviet armies of the 1980s.

For all the misery they have endured, Aghans are remarkably resilient. They are warm and gracious people, openly curious about strangers and solicitous of their needs. Their hospitality is legendary. Hungry refugees in tent camps insisted I share their meager meals with them. Even the poorest families somehow produced tea and beef kabobs when I would arrive, unannounced, to interview them. Even in Mudoh, with its core of furious survivors, a village elder invited me to his bombed-out hut for tea and fruit.

Of the twenty-five sites I visited where civilians were killed by U.S. bombings, Mudoh was the only one where survivors expressed unalloyed hostility to America. At the other sites, there was only a deep and solemn disappointment that a nation they so admired had treated them so callously. Fazel Sedeq, a white-bearded teacher who lives in a village outside Kandahar, described to me a U.S. air strike that killed his wife, son, daughter, nephew, daughter-in-law, and five grandchildren. He spoke of how grateful his village had been when U.S. forces liberated the hamlet from the oppressive grip of the Taliban. And he spoke of the pain he felt for the loved ones he had lost, and for his loss of faith in America. "We thought the Americans were good people. But they just drop their bombs and leave. They don't explain. They don't apologize." Sedez spoke to me at his wife's gravesite, holding a surviving grandson in his arms and fighting back tears. "The Americans have lost the hearts of the people," he said finally. "Who can love America now?"

U.S. soldiers I spoke to in Afghanistan expressed genuine sorrow at the loss of life. Pentagon officials, from Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld on down, have expressed regret for civilian casualties but also have said such "collateral damage" is inevitable in combat. Afghans realize that the casualties were not intentional but were the result of accidents or miscalculations. But U.S. war strategy virtually guarantees civilian deaths. It is a hands-off war, fought from the air, with Afghan fighters as a proxy ground force. In essence, the U.S. decided to risk Afghan civilians rather than American troops.

Many casualties were precipitated by the Taliban practice of hiding behind civilian populations. In the village of Esterghich just north of Kabul, for instance, villagers told me they knew they would be bombed because of Taliban and Qaeda military command and antiaircraft posts there. Yet they welcomed the bombing despite the deaths of forty civilians caught in the barrage along with enemy soldiers. It struck me that many Afghans, so inured to death after two decades of civil war, seemed to make the same cold calculations as U.S. strategists: Sometimes innocents are sacrificed for a greater good. At the hamlet of Qalaye Niazy south of Kabul, fifty-two civilians who had gathered for a wedding celebration were accidentally killed by U.S. air strikes aimed at a huge Taliban weapons depot. "Even if twice as many civilians died, it's still O.K.," Abdul Rahim, a U.S.-backed commander in the area told me even as he mourned the villagers' deaths. "That's the price we have to pay."

As disturbing to me as the civilian deaths was the treatment of Afghan women. Even with the Taliban gone, few women dare to appear in public without a burqa, the head-to-toe shroud required by the Taliban. Even in Kabul, virtually all women on the streets wear burqas — not because of any government decree, but out of tradition or fear of reprisals. Men routinely badger or beat women who appear in public with their heads uncovered. An Afghan woman who returned to Kabul after years of living in New York told me of being threatened and mocked by men for walking bareheaded in public, wearing tight jeans. When she berated a taxi driver for stuffing three women in his trunk while male passengers rode in the back seat, she told me, she was chased and cursed by a mob of men.

When I visited Afghan homes, women emerged from back rooms only to serve tea and food and then disappeared. They did not speak or make eye contact. My translator, Omar, comes from a progressive, Western-oriented family. His late father was a surgeon, and Omar himself attended medical school. When I visited Omar's home in Kabul, his sister-in-law served dinner but, by custom, did not eat with the men. On my fourth or fifth visit to Omar's home, after mentioning that I had never been able to speak to his sister-in-law, Omar persuaded her to join us for a meal. She ate silently, smiling shyly, her eyes lowered.

A few women are attempting to change centuries of suffocating tradition. I met three women journalists who were so outraged by their treatment at the government-run Bakhtar news agency — where they are separated from male reporters by a heavy curtain and a closed door — that they started their own weekly paper, Seerat. In one issue, the paper demanded that women refuse to abide by customs that relegate them to the back of buses and, in some cases, to taxicab trunks. The paper has pointed out that the Taliban provided day care for female government employees, while the new U.S.-backed government does not. "Women's lives have been terrible, but not just under the Taliban," Marry Nabard Aaeen, the paper's editor, told me. Aaeen and the other women who work at Seerat wear long dresses that reveal their calves, but they still cover their heads with scarves. Appearing bare-headed in public would be too provocative, they concede. One reporter, Najeeba Maraam, puts on a burqa to travel to and from the office because she fears harrassment from men on the street. "Peoples' attitudes have not entirely changed just because the Taliban is gone," she told me.

Another subject that raised difficult ethical and moral questions was poppy cultivation. Opium is by far Afghanistan's leading export, pumping millions of dollars a year into the economy. In 2000, the last full year of Taliban rule, the fundamentalist regime managed through terror and coercion to reduce the country's poppy crop by an astounding 96 percent. But in 2002, the first full crop under the new government was nearly back at full strength, with the raw opium to be shipped to Pakistan to be converted into morphine and heroin. Under pressure from Great Britain and the U.S., the new government mounted a half-hearted crop eradication effort that outraged poppy farmers who rely on the crop to feed their families.

There is nothing furtive or shameful about growing opium poppies around Jalalabad. The plants are cultivated openly in lush fields in the verdant countryside and on corner lots in the city. Many homeowners grow poppies in backyard gardens. To a man, the farmers I visited justified growing poppies on the ground that since someone was willing to pay handsomely for the crop, they would be foolish in a country as poor as Afghanistan not to satisfy that appetite. If they did not, they said, someone else surely would.

"Yes, we know it is poison, but have to feed our families," said Said Ehsan Sadat, owner of six acres of poppies.

His neighbor and fellow grower, Abdul Ali, interrupted Sadat and told me: "We prefer to think of it as growing medicine. What do you call it? Yes, morphine."

I asked Maulavi Fazalhadi Shinwari, an elderly Qur'anic scholar who serves as chief justice for the Kabul government, whether growing opium was haram, or forbidden by Islamic law. Shinwari stroked his beard and pondered the question before answering: "We make an exception for exceptional circumstances, such as people living in poverty."

The capacity for violence in Afghanistan fascinated me. It was difficult to reconcile the warm, diffident, engaging men I met everywhere — in shops, bazaars, homes, and military checkpoints — with the civil wars, ethnic bloodletting, and tribal rivalries that have left hundreds of thousands of Afghans dead over the past two decades.

In Bamian, the remote mountainous region that was home to the two massive stone Buddhas destroyed by the Taliban in March 2001, I walked through villages burned and looted by the Taliban. The Talibs had mounted a pogrom against the Hazaras, the Shiite descendants of Mongols. With their Asian features and Shiite beliefs, the Hazaras were considered heretics and infidels by the Sunni fundamentalists of the Taliban. Thousands were massacred in Hazarajat, the Hazara homeland in north-central Afghanistan. I was overwhelmed by the depth of the savagery. The Taliban attempted not only to murder their religious rivals, but to humiliate them and destroy their culture. They raped women and girls. They desecrated cemeteries. They burned and looted mosques. "These Taliban were Muslims only in name," Abdul Rahman Shaidani, the headman of a mountain village called Shaidan, told me as he stood weeping in the charred ruins of his adobe house.

The symbols of the Hazara culture were the towering stone Buddhas, hewed from sandstone cliffs more than 1,500 years ago. The Hazaras had been converted to Islam from Buddhism more than 1,000 years ago, but they still clung to the Buddhas as enduring cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic totems. Said Mohammed, a Hazara elder, was still shaken months later when he described to me how the Talibs — and their Arab and Pakistani explosives experts from al Qaeda — cheered and taunted the Hazaras as the statues crumbled. "They told us: 'We have killed your gods!'" High inside the hollow alcove where the larger Buddha once stood, I found a spray-painted message left by a triumphant Talib: "The just replaces the unjust."

But three years earlier, in northern Afghanistan, where Pashtun civilians loyal to the Taliban were outnumbered in a region controlled by fighters at war with the Taliban, Hazaras and their allies massacred thousands of Pashtuns. In some villages, the severed heads of the victims were left impaled on stakes for all to see. I couldn't help but wonder how many of the Hazara men mourning their murdered family members and beloved Buddhas had blood on their own hands.

The fall of the Taliban and the rise of the Northern Alliance has changed the power equation in Afghanistan, but it has not altered the ancient Afghan code of vengeance and retribution. In Herat, in western Afghanistan, the Tajiks who dominate the region had suffered under Taliban rule. When the Tajik warlord Ismail Khan retook Herat with the help of U.S. airpower and Special Forces troops, it was the Pashtun minority who paid the price. Pashtun men complained to me that Khan's militiamen were killing, robbing, raping, kidnapping, and carjacking Pashtuns, with Khan's blessing. When I sat with Khan in his gilded reception room inside the governor's palace in Herat, I asked him about the allegations. Beneath his thick white beard, a smile played on his lips. "Maybe you should be asking about what the Taliban did for all those years," he said. His meaning was clear: An eye for an eye.

Throughout Afghanistan, my guide was Omar, a slender, fearless man of twenty-five, with thick black hair and a long, solemn face. His late father was Tajik and his mother is Pashtun. He is fluent in the Dari dialect favored by Tajiks and the Pashtu dialect used by Pashtuns. But Omar clearly identifies with the Tajiks, for he and his family had been driven from their home in Kabul by the Taliban. They lived in exile in Pakistan until returning to Kabul in late 2001.

Omar blamed the Taliban's religious fanaticism for driving him from Islam. He still considered himself a Muslim, he said, but did not attend mosque or pray five times a day, as required of devout Muslims. He blamed religion — or the perversion of religion — for many of his country's problems. For now, he said, he was keeping his distance from any religion, though he could not avoid the cultural customs imposed by Islam on a deeply Muslim country. He was curious about my religious beliefs, but unable to comprehend my attempts to explain Unitarian Universalism. He was particularly baffled by the concept of tolerance. He could not believe that I had helped teach a church school class that studied other religions and visited their places of worship. He said he had been raised to believe that people of other religions, especially Christians, were infidels to be pitied or feared. He had never been inside a church, he said, but he had met Christians and liked them very much. When I suggested that perhaps he believed in certain Unitarian Universalist principles but did not realize it, he laughed and hugged me in disbelief.

Omar guided me through daily ethical dilemmas. As a Westerner, I was besieged by children begging on the streets of Afghanistan's cities. They were persistent and aggressive, tugging at my sleeve and tapping at my legs, shouting "Baksheesh! Baksheesh!" — Persian for tip or gratuity. I was tempted to give them money, but Omar stopped me. The children worked for adults, he explained, and were forced to hand over any money they raised. He considered them a blemish on Afghan society, and they embarrassed him. And I embarrassed Omar by occasionally giving in and handing a few crumpled afghani currency notes to children who looked particularly bedraggled. Finally Omar came up with a nickname for me: "Mister Baksheesh."

In Herat, we spent two days with three U.S. Special Forces soldiers who were serving as civil affairs officers, dispensing cash for small humanitarian projects such as rebuilding girls' schools ransacked by the Taliban. Omar helped the soldiers translate as they negotiated with merchants in Herat's bazaars for huge lots of fabric they were buying to donate for hospital gowns. After the soldiers had reached a deal with one merchant for $420, Omar overheard the merchant telling his friends that he planned to substitute a cheaper fabric for the material he had promised the Americans. Omar not only warned the Americans that they were about to be cheated, but he also cursed the merchant. "You think you're just cheating some Americans, but you're cheating Afghans who are supposed to get this fabric!" he shouted at the man. "You're a disgrace. You're what's wrong with Afghanistan!"

Omar was fiercely proud of his country, and he wanted desperately for it to survive and prosper. He helped me seek out heroes helping to bring Afghanistan back from the abyss. We found Alberto Cairo, a manic Italian lawyer who ran a Red Cross clinic in Kabul that treated thousands of land mine victims. Cairo laughed and joked with his maimed patients, cajoling them to forge a hopeful future out of a wretched past. After they were fitted with plastic legs made at the clinic and given weeks of physical therapy to learn to walk again, Cairo gave them a new purpose in life: They took jobs at the clinic, making plastic legs and teaching other patients to walk on their new legs.

We also found Mohammed Ismail, a "grave enumerator," at the Maslakh displaced persons camp. It was Ismail's job to count the number of people who died at the camp. (On average, twenty-nine people a week succumbed to disease, exposure, or malnutrition.) A displaced person himself, Ismail carried out his duties with dignity and respect. He tracked down and interviewed relatives of the dead, carefully logging the particulars of the deceased: name, date and cause of death, home district, and perhaps an estimated age. He consoled the families and helped make hasty burial arrangements. Ismail told me that it was important that each victim be given a name and a personal history in a country where thousands of people died anonymous deaths. "If not, you are only burying a body, not a person," he told me.

We encountered ordinary Afghans fascinated with America, or the concept of America, a country that for them embodied freedom and prosperity. Many people I met said they dreamed of visiting America one day. When I asked what America might offer them and their families, they invariably answered: Peace. They envied Americans for their wealth, their consumer luxuries, and their democratic freedoms. But most of all, they envisioned America as a place where there are no tribal killings, no religious violence, no reason to spend each day fearing for their lives.

Even in a nation scarred by violence and ethnic hatred, Afghans love a good joke. They seek out humor in the most desperate situations, often with a tinge of fatalism. Outside Herat, Omar and I inadvertently drove through a checkpoint without stopping. As we pulled away, we heard two gunshots. We stopped, and a gunman from the checkpoint ran up to Omar's window. "Did you know we shot at you?" the gunman asked. "Yes," Omar said, "but you missed." The gunman so thoroughly appreciated the joke that he apologized for shooting at us and asked us to stay for tea.

In Qalaye Niazy, a pro-U.S. militiaman named Shaneef Shah led us to a Taliban ammunition dump that had been bombed by U.S. warplanes. The flat desert landscape was littered with shredded ammunition cases and shrapnel from rockets, mortars, and missiles. Shah walked casually through the mess, showing us crates of rockets and grenades that were unscathed and still in their protective plastic sleeves. I asked him why he and his commanders hadn't collected the weapons for their own use. "Oh," he said offhandedly, "because it's sitting in the middle of a minefield." Omar was covering his mouth with his hand, trying to stifle laughter, as he and I tiptoed away.

David Zucchino is a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times. He and his wife, Kacey, and their three daughters are members of Main Line Unitarian Church in Devon, Pennsylvania.

![]()

UU World XVI:6

(November/December 2002): 20-28

Copyright © 2002 Unitarian Universalist Association | Privacy Policy | Contact Us | Search Our Site | Site Map

Last updated November 21, 2002. Visited times since October 30, 2002.

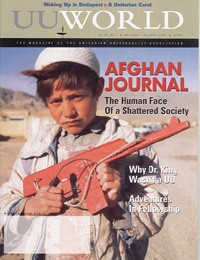

How do we come to grips with the life of the Afghan boy with the red toy

assault rifle who gazes out at us from the cover of this magazine? What

is an adequate response to the human tragedy, political crisis, and

spiritual challenge of the conflict in Afghanistan? More than a year

after the September 11 terrorist attacks, and as the United States military

response enters its second year, what answers are offered by religion,

including our Unitarian Universalist faith? These questions pose an

ongoing challenge, one perhaps never fully answered or answered only

in paradox and contradiction.

How do we come to grips with the life of the Afghan boy with the red toy

assault rifle who gazes out at us from the cover of this magazine? What

is an adequate response to the human tragedy, political crisis, and

spiritual challenge of the conflict in Afghanistan? More than a year

after the September 11 terrorist attacks, and as the United States military

response enters its second year, what answers are offered by religion,

including our Unitarian Universalist faith? These questions pose an

ongoing challenge, one perhaps never fully answered or answered only

in paradox and contradiction.