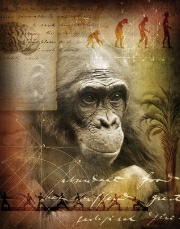

Our inner ape

How deeply rooted is our Unitarian Universalist

belief in peace and justice for all?

We know that one of the essential ways of living the vision and making it real is being healthy in our relationships: being mindful of how we communicate with and about others, seeking a peaceful and constructive resolution process when conflicts arise, celebrating the diversity within our community, building the common good.

Yet this religious vision, and its corresponding commitment to healthy relationships, suggests a question: How deeply rooted is it in our nature?

Teach a dog to fetch a newspaper, and your instruction resonates with a basic capacity that is already deeply instilled in dogs. Is Unitarian Universalism trying to accomplish something similar in us—cultivating potentials that are already ingrained? Or are we more like cats, and a capacity for fetching is just not part of who we are, yet our religion foolishly persists in trying to teach us anyhow?

Scratch the surface of who we are, and what’s underneath? It’s a question that has been asked with great intensity, especially since the savagery of World War II—the willful destruction committed in Europe and Asia by otherwise civilized and scientifically enlightened people. One dominant answer firmly rejected the naïve “onward and upward forever” optimism about human nature that so characterized nineteenth-century liberal religion. In the harsh light of Nazi and Soviet atrocities, this optimism appeared completely ridiculous. What seemed far more realistic was the grim idea that, deep down, humans are basically violent and amoral.

And so, for example, biologist Konrad Lorenz argued that aggression was a pressure within the human psyche that builds relentlessly, completely unrelated to frustrated desires and aims, without understandable or reasonable cause. The inexplicable pressure to destroy is within us, and it just builds and builds until it bursts through the thin veneer of human decency that religions and ethical systems like ours try so hard to shore up, ultimately in vain.

Then there is the thought of science writer Robert Ardrey. His 1961 book African Genesis argued what has since become known as the “killer ape” theory, which is that the ancient ancestors of humans were distinguished from other primate species by their greater aggressiveness, and that’s what drove their evolution. It’s the famous scene in the classic movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, where a fight breaks out among a group of our ape ancestors in which one bludgeons another with a zebra femur, and then that ape ancestor flings the femur triumphantly in the air, where, millennia later, it turns into an orbiting spacecraft.

The “killer ape” theory means we’ve gotten to where we are today through genocide. Says Ardrey, “We were born of risen apes, not fallen angels, and the apes were armed killers besides. And so what shall we wonder at? Our murders and massacres and missiles, and our irreconcilable regiments?” This is who we truly are, says Ardrey. Liberal religion tried to throw away the idea of original sin, but secular science revalidated a version of it. Scratch the surface, rub off the thin veneer of religion and ethics and civilization, and we find something horrible that is nothing less than the secret of our success.

Where do we go from here, if this horrible vision is true? Another movie scene comes to mind, this time from the classic The African Queen. Surrounded by the jungle, Katharine Hepburn’s character says, “Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.” In others words, work even harder to shore up the thin veneer of civilization so that the jungle within us—the inexplicable pressure to do violence—is kept bottled up, pushed down. Sing hymns louder, perhaps; meditate more; repeat the Principles and Purposes regularly and often. Face your fate like a plucky and undaunted heroine, and rise above.

But defying nature only goes so far. Putting on a brave face won’t take away the dread we’ll never be able to stop feeling about ourselves—the sense that there exists a murderous force within us, so alien to all that we hold sacred and holy, so untrue to the teachings of our greatest prophets, so alien to our hopes for peace and justice for all, so irreconcilable with the idea that people have inherent worth and dignity. No inner light within, but inner seething. Therefore we could never truly trust our instincts; constant vigilance is needed to preserve the thin veneer. Not freedom, but authoritarianism, would be the better way in religion and in life. Unitarian Universalism, in short, would cease to make any sense.

What is human nature? Are we really repressed killer apes, or does human evolution teach us something else about our origins and possibilities?

Says Emory University professor Frans de Waal in his fascinating book Our Inner Ape, “If [apes] turn out to be better than brutes—even if only occasionally—the notion of niceness as a human invention begins to wobble. And if true pillars of morality, such as sympathy and intentional altruism, can be found in other animals, we will be forced to reject veneer theory altogether.” Take a look at our closest animal kin—great apes like chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas—and see what their lives are really like. They are what they are, without deception, without shame. So put all the theorizing to the side.

Put “killer ape” theory to the side, and just look at the evidence from the lives of our closest biological kin, with whom we share more than 97 percent of our DNA.

It is undeniable that when we look at our great ape brothers and sisters, some of the things we find are anything but nice. Chimpanzees are notoriously brutal at times, as well as incorrigibly tribal and xenophobic, fanatically patrolling group borders, viciously charging against strangers, and fighting to the death to preserve the group’s territory. But the picture grows far more complex once you consider the larger picture: There is amazing breadth and diversity within our biological family of great apes, and the behavior of chimpanzees cannot possibly represent the final word.

Consider a gorilla like Koko, who has been taught sign language and has her own pet cats. “Koko love Ball. Soft good cat cat,” de Waal reports Koko signing. When her kitten All Ball was killed, she was stricken, as we are when our pets die. Sounding out a long series of high-pitched hoots, she signed, “Cry, sad, frown.”

Or consider the bonobos. “Peaceful by nature,” de Waal writes, bonobos “belie the notion that ours is a purely bloodthirsty lineage.” De Waal tells the story of a bonobo called Kidogo, who suffered from a heart condition and was confused by zookeepers’ commands in his new home:

After a while, other bonobos stepped in. They approached Kidogo, took him by the hand, and led him to where the keepers wanted him, thus showing they understood both the keepers’ intentions and Kidogo’s problem. Soon Kidogo began to rely on their help. If he felt lost, he would utter distress calls, and others would quickly come over to calm him and act as a guide.

That’s the story: the strong helping the weak—genuine sympathy, genuine altruism, found in the sacred depths of nature, right there. Our human heritage, exemplified in our closest animal relatives, is mixed. Chimpanzees may be tribal and xenophobic, but bonobos regularly establish peaceful relations with foreigners. Our inner ape is not just one narrow thing, as “killer ape” theory suggests. What’s deep down in human nature is broad: as much love and compassion as it is murder. And our job is to choose wisely which impulses to draw on.

Our job as humans is not so much to follow Katharine Hepburn’s advice and “rise above” nature as it is to bring into fuller expression certain capacities it has gifted us with, to draw on the positive aspects of our inner ape to make a better world. Hubert Humphrey once said that “the moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy, and the handicapped.” Now if in bonobo society we have the strong helping the weak, why not in human society, and more of it? Why not?

Biologists have documented in bonobos—as well as in chimpanzees and gorillas—kindness and empathy, a capacity for peacemaking and reconciliation, creativity, even freedom—which is evident in Koko’s capacity to tells lies and in her sense of humor. Actors carrying out a pre-set genetic program just can’t do this sort of thing, aren’t capable of the kind of improvisation and imagination that deception and humor require. Story after story opens up our minds to the fact that, as de Waal writes, “our humaneness is grounded in the social instincts that we share with other animals.” Our inner ape is just not a killer ape. Don’t say to me, “scratch an altruist, and watch a hypocrite bleed.” That makes no sense, in light of the facts.

Kindness and sympathy and altruism are not veneer-thin but deep. You can’t scratch them away. They are a gift we share with our great ape brothers and sisters. This means we don’t have to be afraid of ourselves. It means we can replace a feeling of dread with a feeling of wonder. It means that we belong to creation. Unitarian Universalism is real. Our commitment to healthy relationships of trust and compassion is realistic. The animals bring us back to our senses. Koko, who signs herself “fine animal gorilla,” teaches us to say—and gives us courage to say—“fine animal human.”

This article appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of UU World (pages 30-32). Adapted from a sermon preached to the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Atlanta on August 23, 2008. See sidebar for links to related resources.