If it looks like a Universalist . . .

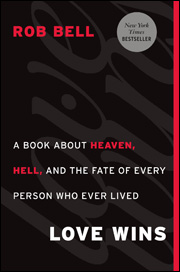

Popular evangelical Rob Bell makes the case for universal salvation.

While his detractors hurl claims of “Universalism” at him as an epithet, Bell himself refuses this label. “I believe in heaven, and I believe in hell,” Bell told the congregation he serves while addressing the controversy of Love Wins, “and I’m not a Universalist because I believe God’s love is so great God lets you decide.” Which is to say that Bell would probably reject the imagery of the Rev. Dr. Gordon McKeeman*, the great Universalist minister, who imagined some people as “dragged kicking and screaming into heaven.” Interestingly, Bell does not limit our capacity to choose to our mortal life on Earth. He imagines that choice as, perhaps, eternal. At the same time that Bell insists that the freedom to choose is a gift that God gives to us out of love, he also argues that, “God gets what God wants.” (Bell’s God is not gendered.)

In reading Bell’s book, it is important to understand the context of his ministry. Bell, 41, is the founding pastor of the 10,000+-member Mars Hill Bible Church outside of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Grand Rapids, home of Calvin College, is one of the strongest enclaves of Calvinist theology remaining in the United States. I take Bell’s book to be the product of his wrestling with and attempting to reconcile God’s sovereignty with our ideas about how salvation works.Bell’s book begins compellingly with a few instances in which he witnesses Christians claiming to judge the immortal souls of others. He describes an art show in which one of the artists uses a Gandhi quote about peace. One of the guests at the show leaves a note on the piece that declares that Gandhi is in hell. Bell also tells of a Christian responding to news of a fatal car accident by asking if the teenager who lost his life had accepted Jesus and then remarking that the young man was certainly in hell. Bell rightfully rejects these judgments as cruel and arrogant. His book refutes the notion that God is like that. We can draw a parallel between the loving God Bell imagines and the hope-filled early Universalists like Hosea Ballou and John Murray. The closest correspondence from our tradition, however, may be William Ellery Channing’s 1820 essay, “The Moral Argument Against Calvinism.” “Calvinism owes its perpetuity to the influence of fear in palsying the moral nature,” Channing writes, leading us eventually to “vindicate in God what would disgrace his creatures.” Channing argues that it is nonsensical to imagine a God whose acts contradict our own highest ideas of goodness, justice, and morality. God corresponds to our better angels; pettiness is not likeness to God.

It is ironic that Bell got sideswiped when he went on television to talk about Love Wins. Bell’s publicity coup landed him on Good Morning America as well as other TV news programs. These appearances coincided with the horrors of the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, which led hosts to ask: So how do you handle the big questions provoked by what we’ve been seeing in Japan? Why would God simply allow this suffering? And, most Japanese are Shinto or Buddhist. Are they condemned to hell? Or, as a more argumentative interviewer put it, “Which of these two statements is true: God is all-powerful but doesn’t care about the people of Japan, or God does care but is not all-powerful?” These questions are at once incredibly simplistic and eternal. They represent the way many mainstream Americans approach questions about God, the afterlife, and the meaning of suffering. They also punctuate the irony that Bell is faced with these questions after he has just published a book that asserts that “God gets what God wants,” that God’s nature is love, and that, like Jesus, we should understand the this-worldly nature of heaven and hell. These questions cannot be answered with sound bites, though Bell, to his credit, offers sound bite answers that are decent. If anything, these awkward conversations demonstrate two realities: First, our culture tends to engage these major stories by asking theological questions about existential realities. Second, there is a widespread thirst for better answers than those we’ve yet been given. These twin realities are the raison d’être for Bell’s book. And, for us, they are a compelling reminder about the necessity of doing theology publicly and popularly. Reading Love Wins, one cannot help but be struck by the conversational informality of Bell’s writing. His examples are drawn almost solely from scripture. He makes almost no mention of contemporary society or historical theology. (He does cite rapper Eminem twice and St. Augustine once.) While my progressive Protestant friend faulted Bell for all he omits, I see this book more as a result of a spiritual epiphany than exacting scholarship. It is Bell searching for a resolution to a part of the Christian tradition that had not added up for him. Can the good news be even better than we imagine?

Correction 8.29.11: The version of this article that appeared in the Fall 2011 edition mistakenly described the Rev. Dr. Gordon McKeeman as deceased. We regret the error. Click here to return to the corrected paragraph.

See sidebar for links to related resources.

Comments powered by Disqus