The empowerment tragedy

Unitarian Universalists remain unreconciled four decades after controversy over 'black empowerment' nearly tore the UUA apart.

At age eighteen, anything one’s mother is involved in is suspect, particularly if, in her enthusiasm, she cajoles you into coming along. First, she dragged me up to the Rev. Jesse Jackson, then into the plenary session. Listening to speeches was not on my agenda; I fled.

The foray with my mother ended my institutional interest in the UUA until I decided to enter the ministry. In spring 1977, my meeting with the Ministerial Fellowship Committee was looming. To prepare, I participated in a mock interview. The only question I still remember is, “Would you have joined BAC [the Black Affairs Council] in walking out of the 1969 Boston General Assembly?” I was eloquently mealy-mouthed and secretly glad I had not been there. Trapped is what I felt, would have felt, and continued to feel.

During the fall of 1977, while I was serving as a ministerial intern in Bethesda, Maryland, I had a conversation with UUA President Paul Carnes. When he asked about the empowerment controversy, I said it was another generation’s fight, and we needed to get over it. A few weeks later, Dalmas Taylor, an African-American UUA board member, called to report that Carnes, in making the point that we needed to move on, had quoted me. Dalmas advised, “You’d better be careful.” Six months after that, I was reunited with the Rev. Mwalimu Imara, an African-American UU minister who had been my youth group advisor in Chicago. Witnessing his outrage at what he saw as the UUA’s retreat from black empowerment, I said to myself, “I’m not going near this,” and decided to focus my doctoral thesis on the Jamaican Unitarian minister Ethelred Brown, who founded a church in Harlem in 1920.

If only it had been so easy. In 1993, I led a history workshop on Diversity Day at the UUA General Assembly in Charlotte, North Carolina. When I got to empowerment, a verbal fight erupted. While preparing a version of this essay that appears in my new book, Darkening the Doorways: Black Trailblazers and Missed Opportunities in Unitarian Universalism, I solicited the opinion of a respected colleague. He replied in support of the BAC: “I defined who I would be in relation to issues of race, in relation to institutional loyalties, in my understanding of to whom and to what I am responsible. That is what places the controversy beyond reconciliation, and keeps it vibrant and vital in my life. . . . [W]hat is at stake . . . is nothing less than an unwillingness to compromise, apologize for, or explain away a deep and abiding commitment that set me on the path I have followed ever since.” That moment in his life enabled him to define himself. Yes. Was it life transforming? Yes. But why should that make reconciliation impossible?

What is going on? Why has it been so difficult for the UUA to come to terms with what happened between 1967 and 1970? What is powering the ongoing acrimony? And why is reconciliation so difficult?

I speak only for myself and about what I have come to understand. I speak also out of disappointment and weariness, anger and amazement that we have allowed this to drag on for forty years. I have come to believe that the only way to move forward is to look upon what transpired as a tragedy. What do I mean? These were all honorable people responding to cultural circumstances not of their making while in the grip of emotional forces beyond their control. These circumstances compelled them to choose between dearly held values, and they brought to their decision making their humanness: lofty hopes and moral certitude, grim earnestness and inflamed passions, some self-delusion, lots of defensiveness, and as tragedy requires, hubris. Conceived of as tragedy, this drama does make sense.

Regarding race, our religious tradition’s attitude during the first half of the twentieth century shifted with the nation’s—as its attitude liberalized, so did ours. We were engaged in, but not at the forefront of, a movement calling for racial justice. In 1963, the GA rejected a resolution that would have required congregations to drop racially discriminatory restrictions from their bylaws. In doing so, the annual meeting chose to reaffirm a bedrock UU principle, congregational polity, over freedom of access. The same assembly overwhelmingly supported a resolution encouraging congregations to practice nondiscrimination, requiring it of new congregations, and creating the Commission on Religion and Race. The ten-member commission included five African Americans and one Latino: Howard Harris, Wade H. McCree, Cornelius McDougald, the Rev. Dr. Howard Thurman, Whitney M. Young Jr., and Gonzalo Molina.

In nine of the ten years leading up to the 1965 civil rights protests in Selma, the GA passed one or more resolutions supporting desegregation, civil rights, integration, and African independence. In 1963, over 1,000 UUs, led by UUA President Dana McLean Greeley, participated in the March on Washington. Thus, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called on “clergy of all faiths” to come to Selma after the savage beating of peaceful protesters on Sunday, March 7, 1965, UUs were ready to respond. Indeed, they already had. On March 6, seventy-two white Alabamans had marched on the Selma courthouse, decrying white violence; half were UUs from Huntsville, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa. By March 9, forty-five UU ministers and at least fifteen laypeople had come to Selma answering King’s appeal. Then, in response to the Rev. James Reeb’s murder—assaulted March 9, he died two days later—another wave of UUs, including the UUA Board of Trustees, arrived. Still more joined on March 25 as the march from Selma entered Montgomery.

African-American UU emotional involvement was high, but their presence was minimal. Henry Hampton, UUA director of information, arrived from Boston on the same plane as Reeb. Dr. John L. Cashin Jr. and his wife, Joan, members of the Huntsville church, also marched. After Reeb’s death, the Rev. Lewis A. McGee, 71 years old, came from California to attend the memorial service. Emerson Moseley from Barnstable, Massachusetts, and his daughter participated in the march to Montgomery. After the initial march ended and white UU Viola Liuzzo was slain, Moseley’s wife, Margaret, arrived as a voting rights worker.

While the beating of African-American citizens on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the deaths of black Jimmie Lee Jackson and white UUs Reeb and Liuzzo galvanized Americans and led to congressional action, Selma marked a sea change in Unitarian Universalism. Five hundred UUs participated, over 140 of them UU clergy—representing 20 percent of the ministers in final fellowship. Across the country, many UUs organized or joined protests and marches. The intensity of the experience transformed them. The consensus about racial justice sharpened. The level of commitment rose. While UUs had been promoting integration and equality of access since the 1940s, Selma signaled the seriousness of the UU concern for racial justice, a commitment reaffirmed when, in 1966, King delivered the Ware Lecture at the General Assembly.

When riots spread through American cities in 1967, these memories were fresh and powerful. The question was how, not if, the UUA would respond to the “rebellion” in black communities, the radicalization of black consciousness, and the further fracturing of a civil rights movement that had never been monolithic.

Some ask why African Americans have not joined liberal religious congregations in larger numbers. Go back as far as you like and you will find African Americans. However, they were often unsought and unwelcomed, scattered in time and place, and, with a few exceptions, never formed a critical mass within a Unitarian or Universalist congregation. Where that happened can be traced to specific, activist ministers and committed congregations in exclusively metropolitan settings that had a significant African-American middle class: John Haynes Holmes in New York City, Leslie Pennington in Chicago, Duncan Howlett in D.C., Rudy Gelsey in Philadelphia, Stephen Fritchman in Los Angeles, Jack Mendelsohn in Boston. The answer is that neither the Universalist Church of America (UCA) nor the American Unitarian Association (AUA) ever gave sustained backing to African-American congregations. Neither denomination backed African-American ministers who might have formed African-American congregations. Furthermore, prior to 1969, only two African Americans held significant positions of power within the denomination: AUA board member Errold D. Collymore and UUA board member Wade McCree. African Americans who were part of the UCA or AUA functioned in isolation, often without knowledge of one another or of the depth of their history within these two faith communities.

Unitarian Universalism never developed forms of worship, liturgy, writings, music, or theology reflective of African-American experience. Black folks came to UU congregations, not the other way around. Therefore, when 1967 arrived, there was nothing around which to build a specifically African-American UU identity and no natural interface with the African-American community. After one hundred years of squandered opportunities, the consequences came home to roost. The chaos that followed was the result of this self-created void.

Who were the stalwart African Americans who nonetheless became Unitarian Universalists? Educationally and professionally, they were similar to most Euro-American UUs: professionals with college educations. Like most UUs, they had left the religion of their birth because they were seekers who cherished religious freedom. Also, their ties with the African-American community were either loose or unassailable enough that they would not have been shunned for joining a white, non-Christian religion. Many worked in white institutions and probably thought of themselves as being in the vanguard of integration. In 1967, based on the denomination-wide response to Selma, they could not help but have elevated expectations.

As rioting engulfed city after city, it became clear that legislation had not addressed African-American poverty or frustration. That was the context for the Emergency Conference at the Biltmore Hotel in New York in October 1967. Thirty-seven of the 150 attendees were African Americans. They made up 25 percent of a gathering in a denomination of which they comprised only 1 percent, hailing from the urban churches in a faith community that was becoming more and more suburban.

Soon after the conference began, thirty-three of the African Americans, including my mother, withdrew from the planned agenda to hold their own meeting. Seminarian Thom Payne, an imposing presence, was posted at the door to shoo white interlopers away. This black caucus met through the evening and late into the night. As they talked, they tapped into the raw emotion hidden behind middle-class reasonableness. They searched for an identity more authentic than the futile attempt to be carbon copies of white people. They saw white liberalism’s emphasis on integration as a one-way street that elevated white and debased black. Civil rights had changed the law but had proven ineffective at remedying black poverty; liberal religion had failed to address the experience of blackness or to settle an African American in a major pulpit. The group called for a new agenda, and by the time they emerged, the Black Unitarian Universalist Caucus (BUUC) Steering Committee had been formed. They insisted that their agenda be voted up or down without debate, and that included a resolution that $1 million (12 percent of the UUA budget) be directed toward the black community over a period of four years.

Although the all-or-nothing tactic worked with the socially committed Euro-Americans at the conference, over the long haul it was doomed to fail—because ultimately UUs are wedded to individualism and reflexively distrust and resist authority, whatever the cause.

The conference sent shock waves through the UUA. Ben Scott, who was there and later became BAC’s treasurer, recalled, “It was also traumatic. I am not the only UU who was irreversibly shaped by it. Thousands were born again. They came to a better understanding of the whole world through the BAC. They came to a thrilling sense of the awesome potential of human society. In our little UU corner of the world, lifelong friendships crumbled, marriages dissolved, careers were ended . . . and congregations factionalized.” Scott’s words only hint at the intensity of the feelings. For many, what happened during the ensuing years would be nothing less than life-defining.

A paradigm shift away from integration and toward black self-determination was taking place, a change for which the UUA was ill-prepared. Some depict this as a failure of vision. The paralysis, however, is understandable. How does one decide whether to support black demands for empowerment and justice, or to respect the democratic process with its vagaries and delays? The Rev. John Wolf, white minister of All Souls Unitarian Church of Tulsa, told his church: “I am forced to choose between two rights . . . democratic procedure . . . [or] the redress of grievances of an oppressed minority.” He then concluded that “it is not a question of right against wrong or of right against right, the issue is wrong against wrong.”

Wolf came down on the side of the BAC; others did not. Among those who didn’t were three powerful black UUs: Judge Wade McCree, vice moderator of the UUA board from 1965 to 1968; Cornelius McDougald, chair of the UUA Commission on Religion and Race that convened the Emergency Conference, a lawyer and former board chair of the Community Church of New York—the UUA’s most successfully integrated congregation at the time; and another Community Church member, Kenneth Clark, the foremost African-American child psychologist in America. A fourth African American, Whitney M. Young Jr., a member of the Unitarian Universalist congregation in White Plains, New York, and of the UUA Commission on Religion and Race, did not seem to have been involved in UU politics. Nonetheless, he saw in the response of whites who supported such demands at a 1968 New Left political conference a new kind of racism. “The white radicals,” he wrote, “fell over themselves trying to comply with the ridiculous demands of the blacks. They gave them half the votes in the convention, approved insulting resolutions, and listened to wild talk that debased the purpose for which they assembled. In doing this they exhibited a subtle kind of racism themselves, for their implicit assumption was that blacks had to be humored and pacified.”

The UUA board meetings following the Emergency Conference were contentious. A decade earlier, a drawn-out process of listening to all points of view and consensus building had led to the merger of the AUA and UCA. Now, as cities burned, there was no time to mediate differences of opinion. Feeling trapped and not really understanding what was fueling the new situation, the UUA board created the UU Fund for Racial Justice with a budget of $300,000 per year, which would be administered by a reconstituted Commission on Religion and Race, and invited BAC to apply for affiliate status within the UUA. From the BAC’s perspective, their overture completely missed the point.

The first National Conference of Black Unitarian Universalists gathered in Chicago in February 1968, with 207 attending. In May, a group of Afro- and Euro-Americans calling itself the Black and White Alternative, later changed to Black and White Action (BAWA), organized in New York City. On April 4, King was slain. In June, the General Assembly met in Cleveland. In the GA business meeting, the BAC funding proposal was placed on the agenda, and in an atmosphere of extraordinary emotional tension, the proponents of BAWA and the BAC competed for the support of the delegates. On the third day of the assembly, the delegates voted 836 to 327 to fund the BAC at $250,000 a year for four years. In the aftermath of King’s death, what white person, given the guilt they felt, was going to vote against a resolution coming out of the BAC? The delegates also voted to give $50,000 to BAWA, over the protest of the BAC.

Following GA, the UUA board voted to give the BAC $250,000 for that year but not subsequent ones. It also learned that all its discretionary reserves had been depleted by the ambitious agenda and vision of President Greeley, then approaching the end of his term. The following spring, the administration recommended that the sum given to the BAC not be reduced. The board supported that position as well as another, not put forward by the Greeley administration, to give $50,000 to BAWA. The BAC objected both to returning to GA annually for a reaffirmation of the commitment made in Cleveland and to the funding of BAWA.

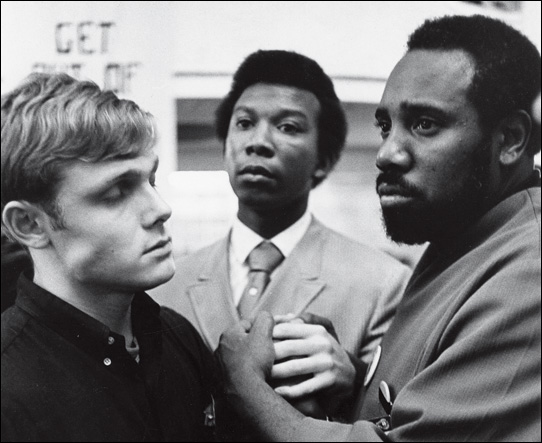

At the 1969 GA in Boston, the Black Unitarian Universalist Caucus (BUUC), the membership organization that controlled the BAC, commandeered the microphones and demanded that the planned agenda be rescinded by vote of the delegates and replaced by a new one that put the BAC funding first. After an unusually bitter debate, delegates refused to accept this change. In response, many BUUC members left. Subsequently, those who supported them also left and regrouped at the nearby Arlington Street Church. A denominational schism seemed possible, but mediation was successful and the delegates came together again. Then, in a vote of 798 to 737, the delegates voted to support the BAC but not BAWA.

The BAC won again and, in that moment, lost. That too makes sense. Good leadership knows about institutional inertia and that conflict is both inevitable and necessary to trigger change. But change is time-consuming, and without leadership, it is almost impossible. Nor can a group move ahead when half is moving one way and the other half another, because force only begets resistance, and when relationships are abrogated, change cannot succeed.

Six months later, under a new president, the Rev. Robert N. West, the UUA board had to face the magnitude of the deficit and, understandably, reconsidered the association’s budget, priorities, and commitments. A million dollars—40 percent of the budget—was cut, eliminating all twenty-one district executives and their offices, while the Office of Social Responsibility was combined with Religious Education to become the Department of Education and Social Concern. The board focused more on survival than justice. Hard choices had to be made. Bearing responsibility for the institution’s viability, the board decided to spread the $1 million commitment to the BAC over five years instead of four. The BAC responded by disaffiliating from the UUA, and the 1970 General Assembly voted to stop funding the BAC, having distributed only $450,000 of the $1 million promised in 1968. But the BAC’s disaffiliation could not have been about the money alone.

It was natural, following King’s assassination, for African Americans to be swept up in a cascade of emotion. Full of rage and grief, and in reaction rather than by choice, many held white people collectively accountable for his death. Alongside that anger and despair was a renewed sense of urgency and impatience with white foot-dragging. African Americans had to lead in the struggle for black self-determination and identity; anything else would have been patronizing and futile.

In addition, middle-class, Unitarian Universalist African Americans probably became suddenly (and painfully) aware of how disconnected they were from the black community. Some probably felt a sense of guilt and needed to reestablish that connection. Proving that their UU community could be relevant was one way. Others felt the need to distance themselves from whites and white institutions. My mother felt this way and left her post at the University of Chicago to teach at predominantly black Kennedy-King Community College. My sister cut off all her Euro-American friends. My brother, who a little more than a year earlier had returned from attending a Swiss boarding school, chose to attend Morehouse College. I joined VISTA to work in the black community. Future UUA board member Norma Poinsett stayed, Alex Poinsett (chair of the Chicago BAC) left. Bac leader Ben Scott stayed, as did Thom Payne, who chose not to be “a part of the UU black empowerment camp.” Future UUA President William G. Sinkford left. Some left in anger. Some left broken-hearted.

Some blame the UUA funding decision for the decline in African-American membership, but that argument ignores the fact that funds were available from other sources and oversimplifies African-American attitudes. In 1972, two years after the BAC disaffiliated itself from the UUA, the Veatch program, through the UUA Fund for Racial Justice, earmarked $180,000 for the BAC. As to African-American attitudes, they were not monolithic. Some told their ministers, “Sorry. I feel torn, but right now I have to put my time into the black community.” Many silently drifted away. For some, anger may have provided a cover for guilt as they did what they needed to do—distance themselves from their white friends. The balance shifted. Affirming black identity became more important than nurturing liberal religious identity. Or maybe their reasons were the same as those of the Euro-Americans who were departing, as overall UU membership declined.

Finally, it makes sense that after forty years, many wish for, but few are ready to seek, reconciliation. Why has there been so little movement toward reconciliation? Because they were all the good guys. They all claim the moral high ground. Having constructed a sense of integrity out of righteous hubris, they recite the ancient justifications whenever they feel defensive. Contrition is for the guilty, and they are not.

All sides felt victimized and misunderstood; they defended principles while others betrayed them. Integrationists felt they were being asked to repudiate their earlier actions and long-term commitment to equality. Also, they were shocked that there was no longer room to hold a different opinion and follow another path, and still be in fellowship. Institutionalists felt they were staving off ruin and preserving the democratic process. The BAC and its supporters felt as though whites were unwilling to put justice first or to trust African Americans with power. For blacks, the “familiar denominational racial routines” echoed the empty promise of forty acres and a mule made to the freed slaves. The result and further tragedy is this: No one who was involved feels understood or appreciated, much less honored.

It is time to honor the passion, fervor, and commitment to principle of all who were involved—and to thank them for caring so deeply. Portraying the empowerment controversy as an institutional failure is short-sighted and misleading. The UUA stumbled, and had to, but it also set the scene for women, lesbian and gay people, the disabled, Hispanics, and other marginalized groups in the UUA to speak out, claim their space, and make demands. These identity groups also experienced resistance, but the outcry was neither as prolonged nor as intense. Who today would challenge an oppressed group’s right to gather together to explore its identity, formulate a strategy, and take a stance? Never again since 1969 has the UUA Board of Trustees, Nominating Committee, or Commission on Appraisal been without significant African-American representation. Never again would we produce a hymnal or religious education materials without reference to African-American experience. The events set in motion by the black rebellion traumatized but also transformed some and educated us all. As Ben Scott said, “The tragedy would have been if successive generations had had to continue to struggle the way they did.”

Unitarian Universalists never stopped trying. Reticently, clumsily, episodically, UUs continue to lurch along. Euro-Americans have come to see that it is their own racism and cultural illiteracy they are called to address. This is what always needed to happen, but reparation—the giving of $1 million to black concerns—however noble, was not meant to address that. In fact, money’s power to assuage guilt may have delayed this white awakening as much as the ensuing trepidation did.

Jean Ott aptly called these events “the white controversy over black empowerment.” In a denomination that was 99 percent white, what else could it be? It happened because of the bigotry and mistakes of earlier generations of religious liberals, because society was forcing change upon religious liberals and change is difficult, because middle-class black UUs needed to redirect their priorities—and this meant, for some, leaving. These were all good people torn by competing loyalties and conflicting values, some of which ran counter to their deepest traditions of polity and individualism. It happened because of institutional immaturity, fear, and hubris. It happened because it had to happen.

Photo: Supporters of the Black Affairs Council commandeered the microphones and demanded a new agenda at the 1969 UUA General Assembly. (Steven H. Hansen, UUA Now/UUA Archives, Andover-Harvard Theological Library)

Adapted with permission from "The Empowerment Saga" by Mark D. Morrison-Reed, in Darkening the Doorways: Black Trailblazers and Missed Opportunities in Unitarian Universalism, ed. by Mark D. Morrison-Reed (Skinner House Books, 2011). See sidebar for links to related resources.

Comments powered by Disqus