Primal reverence

Reverence is an organic human experience

that requires no supernatural explanations.

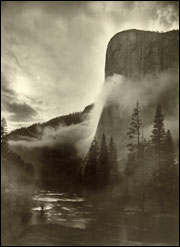

Perhaps for you it is the stars at night, somewhere beyond the reach of our puny, interfering city lights, the whole sky filled with uncountable rays originating from trillions of light-years away, planets and galaxies beyond imagining, made of the same stuff we are made of, and you stand amazed in the shower of brilliance. Or perhaps your taste runs to the deep forest, or the towering redwoods, or the stunning ribbons of color in the Grand Canyon, or the suspense and drama of a thunderstorm, or the reflection of sunset on a hidden lake, or even the first unfolding green of the garden, coming back to life after winter’s severity, or the mystery of a pair of sky-blue robin’s eggs.

Somewhere this planet has a show-stopper for you that takes your breath away and makes you tug on other people’s sleeves to make them see what you see: the whirling autumn leaves with their wedding song of death and beauty; the heartbreaking call of the loon, or the wolf, or the whale; the nuzzling of newborn creatures after the labor of birth, or the struggle of the monarch out of the chrysalis into unfamiliar wings. For me, it is waterfalls. I could stand all day, dumbstruck by the vision of such endless abundance, the living energy of creation poured out unceasingly before my eyes, seeming to promise a truth that something in the world, and therefore something in me, is never and can never be exhausted. It makes me want to weep, want to dance, want to fall on my knees and be one with whatever that is, in everlasting praise.

Let me promise you: As clearly as I am capable of knowing what I know, none of that has anything to do with Jesus. Or Buddha. Or silly people who want to burn assorted writings, or equally silly people who take violent exception to the burning of their favorite texts. The primal experience of reverence in and for the natural world precedes theology of any variety. It is an organic human experience that requires no supernatural explanations. Like everything else about the human condition, our aesthetic sensibilities are a product or a by-product of the evolutionary pressures that have shaped us for reproductive success in our particular ecological niche. If they have any advantage in themselves, why would it not be to help us appreciate our home planet, and find sustenance in its beauty? The visceral response of reverence is as real and as functional to the kind of creatures we are as our hunger, our fear, our sexual impulses, our protection of the young. And just as our hunger and our fear can make us cruel and dangerous, just as our sexuality and our parental concern can be perverted into destructive self-serving, so can our innate capacity for reverence be twisted into oppression and misery.

Perhaps the most essential tenet of liberal religion, across all mythologies and ritual vocabularies, is that each one of us is responsible for what we do with, and about, and because of that experience of reverence. It is not society’s job, it is not our parents’ job, it is not even ultimately the church’s job or any minister’s job, but yours alone, to decide how you will respond to that breathtaking beauty, which consists partly in the recognition that you and the world around you and the creative energy of the whole universe are embedded in the same source, and are in some profound way the same thing.

The primal experience of reverence also comes in the stories of human lives that move us with their courage, with their dedication to justice or beauty, with their embrace of sacrifice for some larger good. It is found in the story of Paul Rusesabagina, the Rwandan hotelkeeper who risked his life to shelter his countrymen from genocide at the hands of their neighbors. It is in the story of Harriet Tubman, leading her fellow slaves to freedom. It is in Gandhi’s witness against the brutalities of British occupation in India. It is in the endurance of Aung San Suu Kyi, living for decades under house arrest and threat of worse in order to offer a democratic alternative in Myanmar. It is in the stunning mercy of Nelson Mandela, leading South Africa’s reconciliation after generations of apartheid violence and oppression.

It is in every mother who has ever gone hungry so that her children might eat, in every soldier who has ever died so that his comrades might live, in every rescue worker who ran up the stairs of the World Trade Center on that awful day. It was in Michael Servetus, who gave himself to the flames rather than deny the freedom and truth of his conscience. And it was in the life of a radical Jewish peasant who called for a community of love and justice that took no account of Roman authority and followed his scorn for oppressive power to the cross. There may be a little bit about Jesus in this one, but he’s not alone, not by a long shot.

One of these stories, or one of the thousands like it, brings a lump to your throat. Somewhere there is a hero—living or dead, close or distant, historical or mythologized—a hero of conscience or mercy, of generosity or duty, whose story whispers to your secret heart, “This is the life you were made for; this is the kind of person you ought to be. Reach for this. Grow into this. Prepare yourself for the moment, you know not when or how it may come, that you will be offered a choice between the nobility that is possible, and the sleepwalking path of least resistance. Learn courage; learn wisdom. Practice the highest values you know. Be ready.”

That whisper, too, is reverence. That lump in your throat is the counterpart of the gasp elicited by nature’s breathtaking beauty and power. Neither one has anything to do with an old man sitting on a cloud with a long beard keeping score. For heaven’s sake, let go of that picture. Even if you are a believer in God, that portrait does your belief no justice. In the name of all that is holy, set that image aside, and start over, with the reverence that is real for you. Perhaps in time it may lead you back to the story of Jesus and the Christian God, and you will, as T.S. Eliot put it, “arrive where you started, and know the place for the first time.” But if not, if that place turns out not to be the home of your soul, then welcome. Welcome to this larger, longer, more pathless journey that we Unitarian Universalists, we humanists, we religious liberals share. I promise: You will not be alone.

So many of our inherited religious traditions want to put the cart before the horse. They want to start with the vocabulary of ritual and the structures of belief before we have a chance to reflect on what it is that actually calls forth the experience of reverence in our bodies and minds, our hearts and consciences. Without that primal experience, all the rest is hearsay; it’s all rote and drudgery and guilt. No wonder we resist it, reject it, find it full of hypocrisy and arbitrary, meaningless rules. No wonder the skeptical mind and contorted conscience rebel, and contend that it must all be nonsense. Good for the mind and the conscience. Good for the heart that will not embrace merciless virtue or saccharine piety. Good for the body that will not deny its hunger, or kneel to authority, or dance for the sake of a rumor. It seems to me that skepticism is actually the most reverent posture there is: the longing to know for ourselves, not to be misled; the willingness to take responsibility for discovering what, if anything, might be actually worthy of our worship, and to give our reverence to nothing less.

We are not skeptics because nothing is sacred. No, we withhold our assent to unproven claims because integrity matters, because the real experience of reverence is so primal and so powerful that it must not be captured and exploited for lesser purposes. Which is all very well, but how then shall we live? Must we simply wait for those flashes of beauty to arrive unbidden, for heroes of the human spirit to appear in our midst, inspiring us with their honor?

This brings us to the question of spirituality for skeptics. It is not just those who are confident of their orthodox certainties who might wish to cultivate the capacity for reverence, to expand the ways in which our lives are enriched through those breathless, lump-in-the-throat moments.

In “Beyond What’s Broken,” Geneen Roth writes about what happens when we stop running our familiar programs about fear and deficiency and emptiness: “I don’t know what to call this turn of events, or the freshness that follows it, but I know what it feels like. It feels like relief, infinite goodness, the essence of tenderness, compassion, joy, peace.” It seems to me that she is talking about a kind of spiritual practice that is oblivious to the vocabularies of tradition. We might call it redemption; we might call it tikkun olam, the healing of the world; we might call it enlightenment, or, as some Native American traditions would, beauty. It doesn’t matter. This, too, is an inherently human experience—the realization of the open secret, that there is no goal, no test to take, no one keeping score; that that which is not broken is always present, whether we have a name for it, whether we are paying attention; and the final recognition that you are—that each of us is, that unshakable truth—and that you have been here all along, waiting for the exiled self’s return. This is what the mystics of every tradition have been saying, in whatever language they could summon to their purpose; it is not a function of any scripture or school, but of the human condition.

Who doesn’t want that open secret to come into focus; that sense of tender, compassionate self-awareness and rock-bottom peace; that return to a wholeness that cannot be achieved, but is there all along, no matter what? This is not the opposite of the hope for growth that the heroes of honor call us to. Indeed, the foundation of all ethics is to be loyal to the truth we know, to the justice and mercy we cannot help but love. How do you become that person, the one who rises intuitively to the demands of the good, who lives in the heaven of the present, who is fed by the beauty of creation? Not, it seems to me, by abandoning skepticism; not by taking someone else’s word for what life means and how we are supposed to live. The skeptic’s path is its own journey, and it can be just as rich in reverence as any more conventional religious structure.

The task of our liberal religious communities is to share the adventure and help each other remember the open secret of our unconditional worth and dignity, even when we doubt it most; and to grow together toward the ideals that arise out of our reverence for the good. Just as we grow and mature physically, and keep ourselves healthy with regular exercise; just as we grow and mature mentally, and develop our minds through learning; just as we grow and mature emotionally, and deepen our relationships by sharing ourselves with others; just as we grow and mature ethically, and build moral character from the values to which we are loyal; so I am persuaded that we also grow and mature spiritually. Religious community exists to help us deepen and celebrate and be nourished by our authentic experiences of reverence.

We gather not because we think we can force those experiences to happen on demand at 11:00 on a Sunday morning—sometimes they do, although you can’t count on it—but rather because we want to remember and affirm them; we want to testify that we are the kind of beings who have such experiences, and that they change us for the better, and give shape to the larger meaning of our lives. It’s one thing to have the night sky take your breath away and leave you feeling both exhilarated and humbled; it’s even better when someone else says, “I know what you mean; I’ve had that feeling, too.” It’s one thing to contemplate with poignant gratitude the sacrifices that were made for the sake of your freedom; it’s something different when a whole community remembers and gives thanks together.

We come together because we are creatures who are fundamentally, physiologically incomplete. As much as our individuality defines us, we also need other people to make our limbic circuits function the way evolution has built us. To the core of our chemistry and our neural networks, we are a social species. Our physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual well-being depends on our connections—both to the world of nature, and to our fellow humans. If we are not part of a con-spiracy, a breathing together, to live and thrive in community on this planet, some essential part of us shrivels up and slowly dies. Spirituality for skeptics is about keeping alive that connective tissue that makes us who we are and enables us to imagine what we might yet become. Some of that work we do alone, in moments of inspiration or insight, but more of it happens in the company of other seekers, those who share the skeptical path with us, insisting on the freedom of conscience and the integrity of doubt. We do it by grappling with the deep questions and the big ideas. We do it simply, by sitting next to each other, by speaking forth our joys and sorrows, by sharing soup, by lifting our hearts in praise of this amazing earth and our astonishing lives, by making music with our blended voices. So let us sing.

This essay is adapted from an address preached April 3, 2011, to the First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis. See sidebar for links to related resources.

Comments powered by Disqus