Home / Issues / Letters, Fall 2011

Letters, Fall 2011

Readers respond to the Summer 2011 issue.

Defining spirituality

Until Doug Muder defined spirituality as “an awareness of the gap between what you can experience and what you can describe,” the word spirituality was a useless word for me (“Before Words: The Spirituality of Humanism,” Summer 2011). It had seemed to only have meaning if you believed in some higher power of some sort. Muder’s definitions opened up a way for me to use the word spirituality that has meaning.

Mae Harms

Garden Valley, California

Muder attempts to define spirituality. It seems to me that “the gap between what you can experience and what you can describe” already has a definition: imagination. His proposed definition of spirituality can then be simplified as “an awareness of imagination,” which could just as easily describe consciousness. If definitions stifle discussion and a dictionary is UU kryptonite, effective communication will be difficult among ourselves and almost impossible with anyone else. In any case, some humanists will always struggle with adapting legacy theistic language (spiritual, God, prayer, worship, etc.) to our naturalistic worldview and wonder why it is necessary. Are there essential UU concepts that absolutely cannot be expressed without invoking this type of vague and potentially divisive language?

Paul Sellnow

Naperville, Illinois

DuPage UU Church

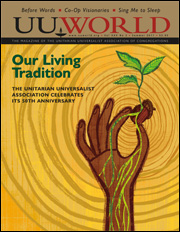

Anniversary pioneers

Thanks so much for the helpful chronology of the Unitarian Universalist Association’s first fifty years (“Key Moments,” Summer 2011). As one of the first wave of women ministers in the early 1970s, I especially appreciated Carolyn Owen-Towle’s remembering of all the work we did to pass the Women and Religion Resolution of l977 and the pioneering work of our “Reverend Mother,” Marjorie Leaming, who founded MSUU (“Doors Opened,” Summer 2011). She was my great mentor and my beloved friend.

But it’s vital also to remember the work done by two laywomen, Lucille Schuck Longview and Rosemary Matson. There were many other heroines of that movement who must not be forgotten.

And we must mention the founding of the Society for the Larger Ministry (SLM), which gave support to those of us wishing to do community ministry at a time when that was still considered heretical. The Rev. Jody Shipley was primarily responsible for the SLM’s founding. One of our early goals was to recognize lay, non-ordained ministries, such as that of our unofficial UU poet laureate, the great composer Carolyn McDade, who gave us “Spirit of Life,” our unofficial anthem.

The Rev. Dr. Linnea Pearson

Interfaith Chaplain and Adjunct Professor of Religion

Florida International University

Miami, Florida

For more on the Women and Religion Resolution, see “Thirty Years of Feminist Transformation” in the Summer 2007 UU World, available at uuworld.org.

—The Editors

I was pleased to read your fiftieth anniversary reports of the 1961 merger resulting in today’s UUA. However, I was astonished you did not mention the clear precedent and model for that merger, fully eight years before, of American Unitarian Youth and Universalist Youth Fellowship into Liberal Religious Youth. AUY and UYF and its successor LRY were led by, and served, secondary school and college-aged youth in the United States and Canada.

Happily, we youth at the time had the support, moral and financial, of the two denominations. We think that our success paved the way for their 1961 merger.

Ralph H. Graner

Richmond, Virginia

First UU Church of Richmond

I was dismayed to read O. Eugene Pickett’s characterization of the “black empowerment controversy” in his account of the UUA’s first five decades (“A Good and Positive Venture,” Summer 2011). His telling of this story blames those who believed in black empowerment for the whole controversy, and for the “devastating effect” this had on Unitarian Universalism. As if Unitarian Universalism were the victims of work against racism, never mind the devastating effects of institutional racism on people of color—both within and outside the white Protestant church. Most disturbing of all is his repeated use of an us- versus-them frame: “Our emphasis on integration” versus their “demands.” This way of framing the story says very clearly that Pickett believes that those who advocated for the black empowerment approach to racial justice within the UUA were not really a part of “us,” not really UUs, not fellow religionists who, though he might have disagreed about strategies, were still a part of a “we” to which he also belonged.

I cannot see that this version of the story will do anything but cause further harm to those who already struggle to be included in our vision of who “we” are as UUs.

I was further dismayed to realize that in an issue presenting the voices of several UUs about different moments in our history, UU World chose to let Pickett’s be the only version of this story. Why is the voice of privilege the only voice that UU World included in telling this story?

The Rev. Erica Baron

Rutland, Vermont

Unitarian Universalist Church of Rutland

posted on uuworld.org, May 27, 11:38 a.m.

Universalism's dream

I appreciated the bold honesty of David E. Bumbaugh’s article “The Unfulfilled Dream” (Summer 2011). He writes, “Our message, our vision, have become confused and unclear.” There is too much dithering about our faith. When asked, “What do Unitarian Universalists believe?” I give my elevator speech, which takes all of one floor: “UUs believe in the divine sacredness of all creation. We acknowledge many names and concepts for God, and we strive to live by Seven Principles to help us be a more loving, just, and compassionate people.” I don’t bother with all the inclusions for varieties of belief that everyone has. I believe that one clear statement gives the person asking a hook on which to hang their comprehension, and it suffices.

Polly Hansen

Deerfield, Illinois

North Shore Unitarian Church

Bumbaugh dismisses our Unitarian Universalist Principles as attempts to market our faith so as to avoid offending anyone. Like many UUs, he perceives them as platitudes, offering no significant challenge to us or to anyone. But they do. Deeper attention reveals the polarities they contain, not only between the First and Seventh, but also within each of the Second through Sixth—compelling yet competing values that invite the engagement of both mind and heart and that will not let us rest. Each of them articulates facets of the profound ethic grounding them all, a dialectic that embodies Universalist theology in real time. Consider: justice/compassion; you’re just fine/keep growing; freedom/responsibility; conscience/democracy; peace/justice. These are deep values that push, pull, stress, stretch, and temper each other. “The opposite of a great truth is another great truth” is how physicist Niels Bohr expressed it. Merging an embracing theology with a rigorous ethic yields a whole-life faith that would compel us to live true, if only we will. Diversity is the vital heart of it.

The Rev. Margaret Keip

Grants Pass, Oregon

UU Fellowship of Grants Pass

I have to take issue with one of Bumbaugh’s frequent contentions. Frankly, he’s not the only one to contend it—it’s been said numerous times in UU World, not to mention many meetings I’ve attended. It’s the canard about Unitarian Universalism having no message. UU does have a unique vision, and one that is desperately needed in this world: It’s that we must treat every human being with both care and respect. That is unique; some other religions may profess it, but they are all built on rules and dogmas that actively deny people caring or respect or both. UUs, on the other hand, actively formulate principles and policies—and reformulate principles and policies—to try to make sure we are the best possible defenders of this faith. And it is our faith.

Steve Jones

Schenectady, New York

First Unitarian Society of Schenectady

The UU principle of respecting the inherent worth and dignity of every person is not a “half-digested cliché,” as Bumbaugh claims. It ought to be a “deep confession of faith” and those who believe in people’s dignity and worth ought not to “stutter and stammer and mutter” when they proclaim it. Advocating for the dignity and worth of every person is not, as he says, a “weak foundation for a religious movement” nor an “inadequate program for saving the world.”

If the principle of the dignity and worth of every person were taken seriously and conscientiously applied in the world, think of the changes that would occur: an end to militarism, poverty, racial and sexual prejudice, and the disenfranchisement of oppressed people.

David Pell

Rochester, New York

First Unitarian Church

UU World welcomes letters to the editor. Send to “Letters,” UU World, 25 Beacon St., Boston MA 02108, or world@uua.org, but do not send attachments. Include your name, address, daytime phone number, and congregation on all correspondence. Published letters with author’s name, city, and state will appear on www.uuworld.org. Letters are edited for length and style; a maximum length of 200 words is suggested. We regret we cannot publish or respond to all letters.