'What ecotourism should be'

An organic coffee farm and ecotourism lodge

founded by a Unitarian Universalist couple

is a model for just and sustainable tourism.

This is Finca Esperanza Verde, a unique experiment in ecotourism and local empowerment. Part organic coffee farm and part tourist lodge, the finca—Spanish for farm—has been spearheaded by a Unitarian Universalist couple with dreams of helping local Nicaraguans find profitable and sustainable ways to share their culture with visiting tourists.

The tourism project was conceived by Lonna and Richard Harkrader, members of Eno River Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in Durham, North Carolina. It grew out of a sister community project the Harkraders helped lead in 1993 that linked churches in Durham with the Nicaraguan town of San Ramón, eleven miles down a twisting mountain road from the finca. When three other North Carolina cities joined the Durham–San Ramón partnership, they became Sister Communities of San Ramón, Nicaragua (SCSRN). The nonprofit plows income from ecotourism and organic-certified shade grown coffee back into the local economy. The chief attractions are stunning scenery, hiking trails, exotic birds, and butterflies—but also the skills and cultural riches of Nicaraguans themselves.

The Harkraders and board members of Sister Communities bought an abandoned forty-acre coffee farm on the mountainside in 1997. Using local materials and workers, the Harkraders and volunteers added a lodge and sleeping cabins for twenty-six visitors, paid for in part by donations from Rotary clubs in North Carolina and other contributors. They have since expanded the site into a 265-acre nature preserve with a very light ecological footprint.

Richard, an architect and solar builder, designed a micro hydro generator powered by a mountain spring that also provides natural drinking water to guests’ cabins. The hydro system and photovoltaic panels on the lodge roof power the finca.

Finca Esperanza Verde—Green Hope Farm—employs thirty local residents who are provided steady jobs with attractive benefits, an anomaly in rural Nicaragua. They get health insurance, retirement benefits, and a month’s bonus at Christmas. Unlike many tourism workers in Central America and the Caribbean, they are employed year-round, not just seasonally.

The staff members teach visiting tourists about Nicaraguan culture, arts, food, history, nature, and wildlife. The finca’s focus on learning from the locals is what distinguishes it from other tourist operations, and from most other ecotourism ventures. Sister Communities, whose members have visited the finca and San Ramón to build friendships with Nicaraguans, calls the trips “cultural immersion ecotours.”

Visitors hike virgin trails and relax over sumptuous finca meals. At the same time, they are also shown Nicaragua by Nicaraguans. When I visited in February with twelve other Americans, including several members of the Eno River fellowship, we were immersed in Nicaraguan culture. Like most visitors, we split our time between the finca and homestays with San Ramón residents.

In town, there were cooking and jewelry-making demonstrations, dancing, folk music, drinks of local rum and beer, a craft fair, and a children’s dance troupe. At the finca, we took bumpy rides in the back of pickup trucks to a coffee farm and a picnic beside a mountain stream. We took nature hikes, went bird-watching, and explored a butterfly reserve.

“Not your typical Mai Tai vacation,” said Jennifer Albright, a Durham resident who was presented with a surprise cake by a finca cook one evening to celebrate her sixty-first birthday.

Another cook, Reina Medrano, showed us Americans how to make tortillas as we took turns cranking a grinder handle and shaping tortillas. Nature guide Humberto Antonio Picado led visitors on mountain hikes, pointing out ancient ferns, reciting the Latin names of butterflies, and detailing the nesting habits of local birds. He also spotted howler monkeys and sloths that visitors didn’t notice on their own. He knows all about the finca’s orchids and tree frogs, too.

In San Ramón, Jesenia Diaz Aviles, a local artisan, showed us how to make raw paper for handmade cards and notebooks. Freddie Rivas, a local jewelry maker, gave a class on creating jewelry from local seeds. And Javier Martínez, a coffee farmer who has learned to grow certified organic coffee, led us through a “coffee cupping,” sampling four local brews.

The Nicaraguans are paid for their time. Among them was Doña Marina Escorcia Pineda, a longtime San Ramón resident who taught an hour-long session on local history. Paid, too, were five local musicians who trudged up the dirt road from Yucul village to play Nicaraguan folk songs around a bonfire one night. One musician persuaded several American visitors to dance around the fire.

María Soledad Avila Escorcia, who has hosted finca tourists in her tidy bungalow in San Ramón the past twelve years, said townspeople are eager to share day-to-day life with visitors.

“The way Richard and Lonna have set things up, visitors are able to see the way people in San Ramón really live. They’re not just tourists—they’re houseguests,” she said.

Through the finca and ecotourism, the Harkraders and Sister Communities have transformed the local community. Before the finca was built, nearby San Ramón had no hotels, no craft sales, no cafés, and virtually no tourism. Many local roads were unpaved, and its water and sewer systems were a wreck.

“The word tourist wasn’t in their vocabulary,” Lonna recalled. “It was a totally new concept. Everybody asked: ‘Why would anyone come to San Ramón?’”

Today, San Ramón is visited by tourists from the United States, Canada, Latin America, and Europe. It has two boutique hotels, a backpacker hostel, several guesthouses, two bar-cum-cafés, a local tourist guide club, and regular crafts sales. The improvements were created and are maintained by local residents, with donations from Sister Communities and others.

The nonprofit has donated money for local communities to build six schools, and other donors provide $500 a year to a dozen rural schools. It has helped fund a maternity center, a home for the elderly, and a guide club run by local teens.

Richard designed the town baseball stadium. Sister Communities, along with Rotary International and Southwest Durham Rotary, donated money to renovate and expand the town’s water system.

“If you build something beautiful, they will come,” Lonna said as she watched local children perform a dance recital inside the tidy little library.

Unlike Westerners who direct most other aid projects, Sister Communities doesn’t dictate who or what receives funds. It doesn’t build projects itself. The nonprofit asks local residents to identify their most pressing needs, then gives grants to groups and communities to run programs and build schools—and leaves it to residents to provide sweat equity.

“It builds a sense of ownership,” Richard said. The goal, he said, is to eliminate the paternalism that dominates many well-intentioned aid projects.

The Harkraders are hardy do-it-yourself types. On their first visit to Nicaragua in 1990, they drove from North Carolina with their two daughters, then 10 and 14. They stayed in Central America for eleven months, donated their car, and flew back home.

In 1997, while building the coffee farm and finca, the Harkraders and volunteers hauled in most provisions in their checked luggage—dishes, towels, linens, and the solar panels for the lodge roof. Early on, visitors and volunteers carried the finca’s green coffee beans home in their suitcases. “We were inventing it as we went along,” Richard said.

Today, Counter Culture Coffee in Durham imports the finca’s coffee beans, roasts them, and provides coffee at cost to Sister Communities. The coffee is sold at Unitarian Universalist congregations, raising up to $23,000 a year. Income from coffee, ecotours, and other tourism covers the cost of operations at the finca—and also funds community development projects.

The finca hires local pickers to harvest coffee beans. It also pumps money into the local economy by buying chickens, eggs, milk, beer, and other products from local vendors. The staff makes juices, jams, marmalades, salads, and other foods from fruits and vegetables grown organically on the finca.

Two years ago, Lonna said, the finca and ecotourism brought $180,000 into the local economy, not counting purchases of food, crafts, and gifts by visiting tourists.

“This is what ecotourism should be. I fell in love with this place the first time I saw it,” said Alex van der Zee Arias, 34, who was hired in February to manage the finca. Van der Zee has managed hotels in Europe and South America and helped run his family’s coffee farm about twenty minutes from San Ramón. But he decided to work at Finca Esperanza Verde because it’s unlike any other tourism project he has ever encountered.

“After working in mass tourism and big hotels, I’ve found the perfect ecotourism model here,” he said.

The finca’s tourism intern is Ian Smith-Overman, 25, a recent college graduate who visited the finca as a child with his Unitarian Universalist family. He’s a fluent Spanish speaker with a passion for Central and South American culture and history.

“What makes this place special is its openness, its shared commitment to the environment—just the whole concept of the human family,” Smith-Overman said.

Praise for the finca’s approach doesn’t just come from people affiliated with it. The Small Enterprise Education and Promotion (SEEP) Network, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit, said of the ecolodge after an assessment visit in 2008: “Finca Esperanza Verde has received international recognition as a model for poverty alleviation through sustainable tourism . . . through an economic model that is self-sustaining.”

The finca won a $20,000 Sustainable Tourism Award for Conservation from Smithsonian magazine. It was named best ecolodge by the Nicaraguan Institute of Tourism and was selected as the model project exemplifying poverty alleviation through sustainable tourism by the World Tourism Organization, a United Nations agency. The Guardian newspaper in London ranked it number one for green tourism in Nicaragua.

Picado, 34, the finca’s nature guide, said he knew little about local plants and wildlife—and even less about ways to protect the environment—when the finca hired him as a coffee worker ten years ago. By learning from visiting biologists and ornithologists, he has emerged as a leading local expert on the forest’s ecology.

He’s also a butterfly expert, thanks to years spent studying the creatures at the finca’s butterfly house, home to a dozen varieties. The finca has sold butterfly pupae to the Museum of Life and Science in Durham—along with some of the leafcutter ants that entertain guests with the intricate trails they build to transport bits of leaves.

“I’m proud to share my knowledge with our visitors,” Picado said. “They seem to appreciate it, which makes me feel like I’ve been successful in life.”

The Harkraders, too, have built an impressive base of local knowledge. Lonna knows the name of every local villager, it seems. Richard, who stomps the finca grounds with a bird guide stuffed in his pocket, can declaim on the distinctions between the orange-bellied trogon and the collared trogon, two of the finca’s 250 bird species.

For the Harkraders, the finca has provided an opportunity to apply their UU values. They are reflected in the commitment to the interdependent web of life, the embrace of the inherent worth and dignity of Nicaraguans, and faith in the collective spirit.

“We are all people of the world—we are all one family,” Lonna said one evening after asking staff members to introduce themselves and talk about their lives. “I often think how lucky I am in my life to be part of something that has had such a big impact—that’s brought the culture of Nicaragua right into the lives of visitors,” she said.

Around the campfire one night, an elderly guitarist, Don Carmelo, prefaced his band’s performance by thanking the Harkraders for “the shared human family” they had brought together at the finca.

The finca is now so successful that the Harkraders encouraged the Sister Communities board to put it up for sale in May. The project “is a large business now and difficult for volunteers to manage,” Lonna said. It will operate as usual through May 2012, she said, with several ecotourism trips booked and space available for other visitors.

No matter who takes over, Lonna said, Sister Communities will continue to provide visitors with what she called “a dynamic cultural immersion experience,” including visits to the same social justice projects in the area.

The Rev. Deborah Cayer, lead minister at the Eno River fellowship, said she was struck by the Harkraders’ unique, inclusive vision when she first heard about the finca. “It was a very different model—an empowerment model and a partnership model,” she said. “It’s a friendship model, seeing people not as ‘those poor people,’ but valuing them and understanding how to open a door for a brother or sister.”

As part of the group that visited the finca in February, Cayer listened as Lonna argued with several local parents who kept their children out of school, saying they were needed to help out at home. Lonna told them, passionately, that every child has a fundamental human right to an education—and the parents listened.

“It was an argument between neighbors, a passionate discussion between equals,” Cayer said. “They’re all in it together. That’s community. Being able to see their inherent worth and dignity, and to respect it—that’s a beautiful thing.”

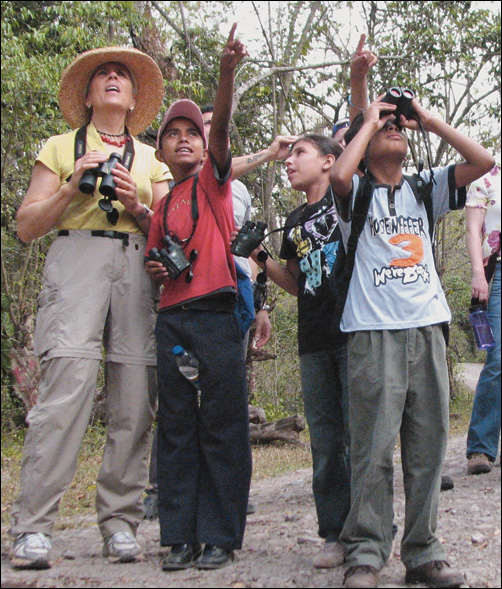

Photo, above, by David Zucchino: Lonna Harkrader (left), one of the founders of Finca Esperanza Verde, an organic coffee farm and ecolodge in Nicaragua, leads visitors on a bird-watching hike.

See sidebar for links to related resources.

Comments powered by Disqus