Sketches of Crete

When a Unitarian Universalist minister moves to the island of Crete, a sense of humor builds a bridge across cultures.

What are Cretans like? Like this. . . .

Asbestos Gelos

My Cretan connection began the summer I was wandering around Europe alone while waiting for my wife to finish her medical residency. No particular agenda—just doing what came next. I went to Crete to see the famous archeological digs at Knossos and to look in on a graduate school program at the Orthodox Academy of Crete. When I was ready to step off the paths beaten down by tourists, I went to a small village at the western end of the island—a fishing village at the end of the road: Kolymbari.

I found a room for the night, and rose up before the sun next morning to go running. The day was already hot, so I dressed only in black running briefs and shoes. (It’s relevant to the story to note here that my hair and beard were white even then.) My route took me past the main kafeneion (coffeehouse) of the village where men sat outside socializing. They ignored me. I was surprised. They seemed surly, hostile, and unwelcoming.

Later, when I mentioned this to my landlord, he said, “Oh no, Cretans are very welcoming to strangers—it is an old tradition—philoxenia. But in your case the men at the kafeneion did not know what to make of you. For one thing, your hair and beard make you look like a priest, but they have never seen a half-naked priest running through the village in what looks like his underwear at that hour of the morning.”

“Oh.”

“No problem. Smile, wave, say good morning in Greek: Kalimera—kah-lee-mare-ah. You will find them friendly.”

“Right.” (Pause.)

See this from the point of view of the men at the kafeneion. They have been gathering here at dawn for years without disturbance or distraction. Suddenly, without warning, the white-bearded, half-naked priest flashes by.

“What the hell was that, Yorgos?”

“Damned if I know.”

“Tourists get weirder every year.”

The next morning I set off running with goodwill toward men in my heart. Ready to greet the villagers. The men at the kafeneion see me. “For the love of Christ, Yorgos, look. Here he comes again.”

Hold the moment. As I said, my appearance was a bit of a surprise in the first place. Then there is the fact of my miserable language skills. During the night my brain changed kalimera (good morning) to calamari, which means “squid.”

And then there was the problem of waving. I did not know that Cretans wave with a gentle gesture of an upheld, closed-fingered hand, backside out, palm in. I didn’t know that the All-American hearty wave—arm extended, fingers open—is equivalent to giving Cretans the finger—“Up yours!” in other words.

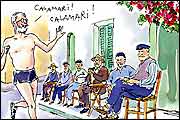

To continue: Here I come. Running by the kafeneion, I shouted, “Calamari, Calamari, Calamari,” and gave my most enthusiastic open-handed wave to all. The Cretans heard “Squid, Squid, Squid” and saw “Up yours!” From the priest in his underpants.

Well. They fell out of their chairs laughing. And shouted “Calamari, Calamari, Calamari” and enthusiastically waved “Up yours!” back at me. More than pleased, I ran on—thinking that these are truly friendly people after all—my kind of guys.

The men in the kafeneion could hardly believe what had happened. “What planet did he fall off of?” they wondered. And of course they did what you and I would do next. During the day they told their friends about the bizarre stranger’s dawn appearance. And when their friends didn’t believe them, they said, “It’s true. Come see. Have coffee in the morning.”

And sure enough, here I come again. I did notice that there were quite a few more men having coffee than yesterday.

“Look, Demetri. I told you. Here he comes. Shout ‘squid’ at him and give him the finger and see what he does.” So they did and I did and so on. Funny. Rowdy laughter all around.

As I ran on by, I turned and gave them the All-American sign for “OK”—thumb and forefinger forming a circle. They laughed even harder and gave me the “OK” sign back. Wonderful!

Word gets around. “You’re kidding.” “No, come see.” The next morning, even women and children were there to greet me.

But that same morning, just after I passed the coffeehouse, a middle-school English teacher stopped me in the street. Serious young man, visibly upset. “Excuse me, mister, you are making a jackass of yourself, and those idiots at the kafeneion are helping you. You should all be ashamed. You are setting a bad example. What will the children think?”

“What’s wrong? What have I done?”

“In the first place,” he said, “no self-respecting Cretan man would ever go out of his house and into the village dressed as you are. Immodest.” He went on to distinguish between calamari and kalimera, and explained the fine points of correct waving.

Finally, he wanted me to know that the sign for “OK” in America was the sign Cretans use for telling someone to stick their head up their own rear end. A road-rage gesture in Crete. A serious provocation that could lead to shots being fired. He conceded that good friends might use it as a perverse joke. But strangers? Never!

I felt bad. I glanced back at the men at the kafeneion. Sheepish grins. Now they knew I knew. And I knew they knew. And so, now what?

I walked away puzzled: Should I leave the village, find another running route, apologize, what? But I couldn’t ignore one unambiguous fact: the laughter. What had happened was funny. The laughter was real.

Actually, my best American best friends and I would have reacted in the same way. These Cretans still seemed like my kind of guys. During the night my brain sorted out the problem.

At first light it was clear in my mind what to do. I donned my running shorts and added to my costume a T-shirt with the blue and white Greek flag on it. Here I come.

Solemnly, the coffee drinkers watched me approach. No gestures. As impassive as the first morning. “Look, here he is again, Yorgos. What do you think he will do now?” “Is he angry with us?” “Who knows?”

To prepare for this occasion, I had asked my landlord how to insult Cretan men in the way that’s permissible only among good friends—the grossest thing—trusting they know you are kidding.

“Call them malakos—masturbators—and slap the palm of one hand on the back of the other hand, with arms stretched out in front of you. It is, shall I say, a suggestion of masculine inadequacy.”

As I got to the kafeneion, I slowed down.

I stopped. Faced them.

A tense moment. Friend or foe?

I smiled. “Calamari.” Then I waved, American style: “Up yours!” And growled malakos at them while slapping my palm against my wrist. To push matters closer to the edge, I made a circle with my finger and thumb. And stood there grinning, but with heart pounding—afraid I just might get the hell beat out of me.

The kafeneion erupted with laughter and applause. A chair was provided. “Come, come. Sit.” Coffee, brandy, and a cigarette were offered. And with their minimal English and my feeble Greek we retold and re-enacted the joke we had made together—from their point of view as well as mine. Above all, they thought my way of handling the situation—in your face, with humor—had Cretan style. Arrogant. Only a true friend would be so audacious.

I was, after all, their kind of guy—and they were mine. It seems there was an opening for Village Idiot, and I filled it.

That was the beginning.

For a long time they knew little about me except that I was a fool and a laugher who understood something about the humor and social courage of Cretan men. To me they became friends with names like Yorgos, Manolis, Kostas, Nikos, Demetri, and Ioannis. To them I became the Americanos, Kyrios Calamari—the American, the honorable Mr. Squid.

As I say, I have been going back for more than twenty years. They have included me in the life of the village—feasts, weddings, gossip, baptisms, wine-making, and olive harvests. My clumsy Greek amuses them still.

I return each year in part because I expect laughter—from their timeless jokes and stories that are often raw and reckless and wicked. Jokes about old age and sex and war and stupidity—jokes that mask fear and failure and foolishness. Their laughter is not cautious. Without this laughter the Cretans would not have survived their travails and tragedies across the centuries. Cretan laughter is fierce, defiant laughter—an “Up yours!” to the forces of death and mystery and evil.

They have a word for this laughter: Asbestos Gelos. (As-bes-tos yay-lohs.) A term used by Homer actually. It literally means “Fireproof laughter.”

Unquenchable laughter. Invincible laughter.

And the Cretans say that he who laughs, lasts.

And they have been around a long, long time.

In the Flow of the Mud and the Light

A Greek couple—dear friends of mine—made their first baby this year. “Come look,” they said. I looked. What could I say? Most babies look like Winston Churchill without his cigar. Even the best ones look like Winston Churchill after a face-lift. This one looks like the daughter of Barbie and Ken. Perfect. That’s what I told the parents. Men usually say, “Beautiful.” Women usually say, “Cute.” But I get very high points for saying, “Perfect.” And not mentioning Winston Churchill.

I wondered what the baby thought when it stared back at me. My God, another big weird-looking thing. Are they all this ugly? No wonder babies scream and cry a lot.

I didn’t know this baby’s name. A Greek child does not have a formal name until it is baptized. And that event takes place somewhere between one and two years of age. A child is carried into the church, stripped naked, handed over to the priest—a stranger in a black dress—and lowered into a tepid bath. The child is usually terrified, goes red and rigid, screams, and often pees. Much to the amusement of the Greeks. It’s not as bad as it seems. It’s worse. I have been a witness. I tell you what I saw.

Ah, but what right have I to speak critically of such things? Me, a heathen, heretic, and certainly neither Greek nor Orthodox.

I speak as an insider. Once upon a time, I was baptized. According to the rules of the church of my childhood. Not sprinkled like the Methodists as if you were going to be ironed. Not just dipped in an indoor pool for the sake of convenience. Baptized according to scripture—outdoors in a river, following the example of John the Baptist and Jesus.

My mother was a serious Southern Baptist. And her cousin from Muscle Shoals, Alabama, urged her to take no chances and do it right. The cousin, it seems, was a “Two-seed-in-the-spirit, Foot Washing, Flowing Water Baptist.” When she sang the old hymn, “Shall We Gather at the River,” it wasn’t about a picnic.

The summer I was twelve, dressed in white shirt and pants, I was properly baptized in the Brazos River—more formally named by the Mexicans, “Brazos de Dios”—the Arms of God. My mother was pleased. I was not. I was scared. My uncle Roscoe had told me to stay out of the river because there were alligators and poisonous snakes in it. But I lived. Was thereby “saved.” And was told I would therefore be going to heaven. When I tell the Greeks about my baptism, they are impressed. Like I’ve got a platinum membership card. An insurance policy that can’t be canceled.

I don’t believe one can save one’s soul. I don’t know what that means. I believe one can only live one’s life, saving nothing, spending it well. But it’s comforting to have my after-life contingencies covered.

And. If it should prove to be the case that there is a heaven and I go, I imagine my mother pointing me out in the great golden hall. “Look, there’s my boy, Bobby Lee! He may have lost his mind when he grew up, but he was properly baptized and so he gets to sit very close to the front. The dippers and sprinklers and child-washers are way back there—up in the bleachers.”

Don’t get me wrong. Baptism is a serious spiritual ritual. No disrespect intended. As a metaphor for re-awakening, it can be meaningful if it makes you think about keeping your path on this earth a righteous one. And that’s a good thing, no matter which religious club you join. There are many ways. Some wet. Some dry. Some lost. Some found. And if the Way works for you and for the commonweal, then do it.

The great Law of the Conservation of Matter and Energy says nothing is ever lost. Everything is saved. Everything comes and goes. It only changes form. Water is essential to life. As is earth, and energy. We exist in the flow of the mud and light.

That I believe.

Megalo Pascha, April 2004

Suddenly—everything happens all at once.

One day it is cold and windy and raining. And the Cretans are sluggishly enduring the last dull days of winter. The next day the weather turns warm, the sky blue, the land green, and the flowers explode from the soil. And the next day it is Megalo Pascha—Easter-doubled plus Passover—the rare calendar event when the Orthodox Church and the Western Christians and the Jews celebrate a holy day at the same time.

Suddenly—in the towns and villages you hear German, Italian, English, French, and especially this year, since Greece is a hot ticket, Hebrew. Four charter flights a day from Israel.

Suddenly—those Cretans who make their living from the tourist industry go mad trying to handle in one big week what is usually spread out over at least a month. The rental business rises like a high tide along the roadside from the town of Chania—cars, mopeds, bicycles, peddle boats, rooms, tours, whatever—and what is not for rent is for sale. Shops and restaurants that were shuttered and deserted last week are in full operation, and Zorba music fills the air all the way to town. Opa!

Suddenly—there are lambs to slaughter and sweet breads to bake and clothes to buy. The churches and the monastery are decorated and everything that should be whitewashed is whitewashed—curbs, trees, walls, big rocks, and steps.

Between now and Pascha, the pace of life will intensify. Relatives are on their way already. The house must be cleaned. The garden must be tended. New clothes must be bought. Delight is the order of the season. And the only scandal is in not participating.

May no scandal be attached to my name!

Suddenly—it’s midnight and the bells ring and fireworks are lit off and the feast is on. Pilafi, horta, paidakia, kokoretsi, kalitsounia, tsikoudia, oenos, and fruita. Christos Anesti! Chronia Pola! Eat! Eat! Eat!

And how would you be certain you had taken part? If you wake late on Monday morning from satiated sleep to find your pillow wet from drool, because your body has been too enfeebled to move during the night;

If your bedroom smells like grilled meat, mown grass, charcoal smoke, and the vinegary vapor of village wine;

If your jeans and shirt on the floor are stained with blood, soot, grease, tomato pulp, chocolate, yogurt, and strawberries;

If the pockets of your jeans contain shards of crimson eggshells, balls of gold and silver foil, and half a candy rabbit;

If the face you see in the bathroom mirror is blotched florid orange and pink and red, and the end of your nose, your cheeks and ears, and the back of your hands are swollen and sunburned;

If your eyes are bloodshot from smoke, and wine in excess;

If your head feels like a baked pineapple and your tongue seems too big for your mouth;

If your hands sting when the soap washes over the many small wire cuts you got from clumsily binding a small bleeding lamb’s corpse to the souvla, the long pronged steel turning rod;

If your wrists and elbows and shoulders ache from turning the souvla over the coals for three hours;

If your abdominal muscles hurt from laughing, and your stomach seems swollen as if you may never need to eat again;

If you cannot remember your real name, but you think it may be Yorgos or Demetri or Kostas;

If the front door of your house is hung with a limp wreath of daisies, poppies, and wild rosemary;

If all the dishes you own and some you do not are stacked unwashed in the kitchen sink, and there are heaps of uneaten cookies and cheese pies and the cold charbroiled head of a lamb on the counter;

And if you feel awful, but you don’t really care, because you know why, and it is a wonderful awful, beyond all sense and reason;

Then you have strong evidence that you have survived Easter Sunday in Crete with friends; that you have helped dig the pit, spitted and cooked the lamb, eaten the wild greens, sopped up the oil with bread from a wood-fired oven, lain on old carpets in the green meadow under the almond trees, chased small children around the fields, drunk far more juice of the vine than hospitality required, and laughed and laughed and then laughed some more before falling asleep in the sun, and somehow finding your way home, to fling your clothes onto the floor and your body into your bed.

You have been Eastered to the max, Cretan style. Megalo Pascha!

You will have done your part. No scandal will be attached to your name.

And despite how you might feel before at least three cups of black coffee on this late morning after, you will know that it is you who have died and been reborn—in the countryside of Crete—not far from the deep well of reckless delight.

If Jesus does come back some glorious Easter Sunday, it will be here.

So declare the Cretans.

And then—suddenly—it’s all over. It is the Monday after Pascha—a day of recuperation for the Cretans and a day of return for the tourists. The ferries and charters haul most of the visitors away. Tomorrow the island eases back into a pace of siga, siga—slowly, slowly—from now till inevitable summer.

For all this fassaria—this general fuss and bother—ancient calmness remains. It is April. The blood-red poppies cover the hillsides here in this far end of western Crete. The monastery bells still mark the hour at six o’clock, followed by the baa-ing of the sheep trudging homeward along the road below my house at dusk, their bells binging and bonging as they go.

Small owls call as evening fades over the wine-dark sea and snow-capped mountains. A warm breeze wanders over from Africa and into the hills of Crete, spreading the usual perfume of orange blossoms along the shore. At dawn the fishermen will go out in small boats and cast their nets in the sea, as fishermen have done for thousands of years.

Wide awake in the deep silence and darkness of the post-Pascha night, I got up out of bed at three a.m. and went out on the porch to see if everything is all right.

For the time being, it is.

Adapted from What on Earth Have I Done? Stories, Observations, and Affirmations by Robert Fulghum. Copyright ©2007 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC. See sidebar for links to related resources.