The Pentagon Papers and me

Beacon Press published the Pentagon Papers a decade before I was born, but Beacon's courage still sets an example.

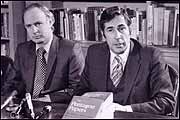

The New York Times and the Washington Post broke the story of what became popularly known as the “Pentagon Papers” in June 1971. Four months later, Beacon Press published the first full collection of the documents as The Senator Gravel Edition of the Pentagon Papers: The Defense Department History of United States Decisionmaking on Vietnam. For longer than I’ve been alive, Ellsberg has been agitating for government transparency; the famous whistleblower has been arrested about 70 times. This week marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of the publication of the Beacon edition, on October 22, 1971.

But why do I find Ellsberg’s words so relevant? I’ve never been arrested. I missed the Vietnam War by a wide margin. I may be the only person my age who owns the complete, four-volume set of Beacon’s Senator Gravel Edition, but when I take them down off my bookshelf I handle them gingerly, aware that their yellowed dust jackets tear easily and cannot be replaced. As documents, I find the Pentagon Papers dated and dense. As symbols, though, I find much in them as important as the day they were printed.

A year ago, I had only a passing familiarity with the Pentagon Papers: way back in the day, these documents had threatened the establishment, or something like that. Then, entering my second year of a Master’s program in publishing and writing at Emerson College, I read A Brief History of Beacon Press by Susan Wilson, which commemorates the publisher’s 150th anniversary. It mentioned the Pentagon Papers several times, hinting at a much deeper history.

As a student of the publishing industry, I was transfixed by a moment of professional courage; as a researcher, I needed to know more. I spent the last year learning everything I could about Beacon Press and the Unitarian Universalist Association’s role in publishing these important documents. My Master’s thesis, a history entitled “Beacon Press and the Pentagon Papers,” is being made available on Beacon’s website. (See link in the sidebar.)

For many people, the story of the Pentagon Papers begins with Ellsberg and ends with “The Day the Presses Stopped,” in June 1971, when the New York Times and the Washington Post were enjoined from further publication of the papers in a case that was resolved by the Supreme Court. For me, that’s where the story begins.

When Daniel Ellsberg handed the Pentagon Papers over to the Washington Post, he did it upon the condition that journalist Ben Bagdikian would deliver another set to Senator Maurice “Mike” Gravel, Democrat from Alaska. Gravel intended to read from the papers during a filibuster of a bill that would extend the draft. Blocked from filibustering, Gravel instead read from the Pentagon Papers during a late night meeting of a subcommittee he chaired—officially entering the papers in the public realm. Believing that “immediate disclosure of the contents of these papers will change the policy that supports the war,” Gravel wanted to make the papers widely accessible to the public and sought a private publisher to distribute them.

Dozens of commercial and university publishing houses rejected Gravel’s proposal, citing near-guaranteed political persecution and a bleak bottom line. Gravel, one of just two Unitarian Universalists in the Senate, then tried Beacon Press, a department of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Beacon’s antiwar list in those days included Howard Zinn’s Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, Jean-Paul Sartre’s On Genocide, and Arlo Tatum and Joseph S. Tuchinsky’s Guide to the Draft. Ideologically, the press felt compelled to publish and agreed to take on the Pentagon Papers, despite great financial and political risks. As a result of publishing the papers, President Richard Nixon personally attacked Beacon Press, the director of the press was subpoenaed to appear at Daniel Ellsberg’s trial, and J. Edgar Hoover approved an FBI subpoena of the entire denomination’s bank records.

Like the government’s case against the Times and the Post, the case against Beacon was resolved in the Supreme Court. Unlike the newspapers, Beacon Press lost: The Court ruled that Gravel’s immunity as a senator did not extend to his publisher, leaving the press vulnerable to prosecution. While he was not in the majority, Justice William Douglas concluded:

The story of the Pentagon Papers is a chronicle of suppression of vital decisions to protect the reputations and political hides of men who worked an amazingly successful scheme of deception on the American people. They were successful not because they were astute but because the press had become a frightened, regimented, submissive instrument, fattening on favors from those in power and forgetting the great tradition of reporting.

In June 1972, the Watergate break-in drew the FBI’s attention, effectively ending the government’s campaign of intimidation against Beacon Press. Then-director of Beacon Press Gobin Stair called the Pentagon Papers epic, “A watershed event in the denomination’s history and a high point in Beacon’s fulfilling its role as a public pulpit for proclaiming Unitarian Universalist principles.”

There are occasions when I am awed and saddened by the parallels between past and present. One such moment struck me when, sitting quietly in the archives at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, I read a statement by the Rev. Robert West, who was president of the UUA when the Senator Gravel Edition came out: “We believe that in publishing the full version of the Pentagon Papers as made public by the Senator last June, we will help reduce the likelihood of our nation becoming involved in a similar situation.”

Later, I held West’s words up against those of Howard Zinn, who in 2002 said: “There’s nothing comparable to The Pentagon Papers today . . . that would blow the whistle on what are the secret things that are being said and done by the government in the so-called war on terrorism. . . . It would be very nice if somebody did for what is happening now, what Ellsberg . . . and what Beacon Press did, at the time of the Vietnam War.”

Again and again, I try to gauge the success of the Senator Gravel Edition. Beacon Press was nearly bankrupted by legal expenses, but financial support from the Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock and many smaller donations from individuals kept it afloat; happily, the press is thriving today. But the larger impact of the Pentagon Papers remains hard to quantify. Publication helped set legal precedents involving constitutionally demarcated congressional and executive powers. Beacon’s example held accountable an increasingly corporatized publishing industry that, by kowtowing to political pressure, abdicated editorial responsibility. Government intimidation of Beacon and the UUA drew attention to President Nixon’s willingness to flout the law to destroy his enemies. The Pentagon Papers themselves exposed U.S. policymaking as often no more than rubber-stamped racism, which held little regard for the welfare of the citizens of an occupied nation. Sound familiar?

When I look at the Pentagon Papers, I trace the handovers: From a Pentagon insider setting a course for change, to a now-venerable journalist, to an upstart young senator, to a fiercely independent publishing house, and finally to me. What connects us is more than a paper trail—it’s the legacy of a line drawn in the sand. This is the line on which our government is built: the accountability those in power owe to those they govern. Thirty-five years ago the Pentagon Papers showed us that trust in our highest elected office may be betrayed. Now, in 2006, I find that these books still have much to say.

This essay is adapted from Beacon Press and the Pentagon Papers by Allison Trzop. Originally submitted as a Master’s Project to Emerson College, this study is now available online at www.beacon.org. An anniversary celebration and forum on the enduring lessons of the Pentagon Papers are scheduled for General Assembly 2007 and will feature Daniel Ellsberg.