UU legislative ministries now in 15 states

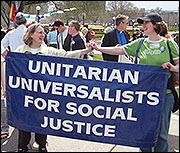

State legislative ministries bring UU values to the public arena.

It was such a network in Minnesota that helped block an anti-gay amendment to the state constitution in 2006. That same year the network helped pass a renewable energy measure. In Massachusetts, a UU network helped keep thousands of units of affordable housing for low-income residents from being converted to market-rate housing.

Groups of UUs and clusters of congregations have often worked together to make the world better. But in the past decade networks have become more formal. Much of this effort started with the UU Legislative Ministry California (UULMCA). Organized in 2004, the UULMCA has been one of the most visible and successful state UU networks. It has been a key player in the fight for marriage equality in that state and has also had an active role in climate change and health care reform issues.

UULMCA was organized by UUs who felt that their faith called them to work to change public policies that harm people and the environment, said Mary Foran, who is serving as interim director while Executive Director the Rev. Lindi Ramsden is on sabbatical.

“We’ve spent a lot of time figuring out how to be visible, both in the public eye and in congregations,” said Foran. “We help people go beyond clicking on an email. We help them become more engaged, to understand the complexity of issues, and to do this in the company of others so they have an enjoyable experience.”

Inspired by UULMCA’s success, UUs in 14 other states have formed networks for the purpose of lobbying for social change. They are in California, Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, and Missouri. Several others are working on forming groups.

These networks have their own organization, UU Statewide Advocacy Networks. Nancy Banks is the paid coordinator for the organization as well as the executive director of UU Mass Action Network, the state group in Massachusetts.

“The key thing we do is effectively mobilize people in congregations to get their voices heard in the public arena,” said Banks.

There are lots of different ways of forming networks, she said. In Maryland, one congregation, the UU Church of Annapolis, was the organizing force. In Minnesota the UU congregations in the Twin Cities provided the initial effort. In Massachusetts it came from a group of individual UUs. In Florida it was spawned by the UUA’s Florida District office.

Starting a network is pretty basic, said Banks. “You go out and talk to churches and ask them to join. It’s true grassroots organizing. It takes a lot of volunteer effort.” About half the networks have a paid director. The networks range from having no budget, to UULMCA’s annual budget of around $160,000. “If you’re going to have any staff you need at least $15,000 to $30,000,” said Banks.

Raising money is a challenge for all networks, she noted, adding that few state coordinators are paid adequately. “Many of them are paid for 10 hours and work 20. Adequate funding is our greatest challenge.”

In Minnesota, a short-term campaign 11 years ago to work on homelessness issues has evolved into the Minnesota UU Social Justice Alliance (MUUSJA, pronounced “Moosejaw”). It helped turn back a conservative campaign to add an antigay amendment to the state constitution. In 2006 it successfully worked for the passage of a state requirement increasing the amount of renewable energy to be used by the state by 2025. This past year it was engaged in election integrity work, helping to ensure a fair vote recount in the Al Franken-Norm Coleman race for the U.S. Senate. Other issues include anti-bullying and racial equity in public contracting.

MUUSJA has a $28,000 budget, mostly for staff time. “Our goal is $60,000,” said Ralph Wyman, the network’s half-time director. As in most networks, he is the one who researches issues and coordinates volunteers in bringing pressure to bear on elected officials.

Giving volunteers the information they need enables them to get out and lobby, he noted. “There are lots of folks in any state who have a depth of knowledge and the ability to engage the political process if they are invited in a way that uses their time effectively. Most people can’t take time away from their day job to sit with the county commission to talk about hiring goals for a light rail contract, but they’re happy to show up for a lobby day or other event if you give them the information they need.”

The Rev. Carol McKinley is half-time coordinator of Washington State UU Voices for Justice. It holds an annual legislative conference, inviting a legislator to speak, and inviting all UUs to attend. It also names a legislator of the year every other year. The group helped win passage in 2009 of a domestic partners benefits bill, and is working to repeal the state’s “Defense of Marriage” act. It is also working on tax reform and clean water issues and for greater disclosure on payday loans. It has a budget of about $16,000, including a $5,000 stipend for McKinley.

She added, “If we didn’t exist there would not be a statewide awareness of specific issues around a liberal faith perspective. We are required as religious people to step forward and speak out and act on these issues. We emphasize to our congregations that it’s important for them to take on the practical needs of the poor. But it’s imperative that we also work for systematic change.”

In 2009 the state networks commissioned a study to determine how they could be more effective, and what their role is in UU social ministry.

The Rev. John Gibb Millspaugh completed the study this fall. He found that state networks generally have a strong relationship with two-thirds of the congregations in their respective states. Cumulatively, that means nearly a third of all UU congregations are touched by a network.

Millspaugh had four recommendations for state legislative networks.

First of all, he found there was little awareness of the state networks by other UU justice groups. “Their stories are astonishingly unknown,” he said. He advised state networks to develop storytelling techniques—the creation of “narrative frameworks” that would showcase their work. He encouraged them to use social media more fully. Only three networks have a presence on Facebook, he said.

His second recommendation was for greater collaboration among the networks, the Unitarian Universalist Association, the UU Service Committee, and other justice-seeking organizations. He also suggested that the networks hire a full-time national network organizer since most networks focus almost entirely on state issues.

Millspaugh’s third and fourth recommendations are that the networks seek increased financial support from congregations, individuals, and grant-giving organizations and that they develop more effective governance structures.

He concluded that state networks have the potential to draw people into UU congregations. He cited the experience of one minister who reported that when members of his congregation worked on a ballot initiative it led 42 people to find and join that congregation over a two-year period. The networks also help to change social policy.

The groups also help UUs deepen their faith. “The networks are not simply advocacy organizations,” says Millspaugh. “They equip UUs to discover and articulate their UU values, faith, and identity. Participating in any SAN program equips UUs to live this faith in a new way and transform and deepen their commitment to this faith as a result.”

Comments powered by Disqus