'True to my lineage'

The Rev. Mark Morrison-Reed's quest for spiritual integration.

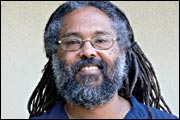

From the moment he walked in from the cold, wearing long graying dreadlocks, a bushy beard, and a plaid flannel shirt, Morrison-Reed exuded warmth.

Making little delighted noises at the unexpected room full of “history junkies,” he asked each person to tell a bit about their memories of encountering race. For an hour, stories poured forth: of a chance meeting with the descendants of a great-grandfather’s slaves, of being beaten up at an integrated high school, of the church’s own leadership in welcoming Afro-Americans and working on gang violence. And so did the tears.

Choked up by a story, Morrison-Reed put a hand to his heart and looked upward. “I’m sorry, this always happens to me. I cry all the time.”

Already late for his next meeting, still he begged to hear from everyone. The last to speak, Don Lyon confessed, “I have a nasty, embarrassing one.” The youngest of four kids in Akron, Ohio, he came home for lunch with his siblings one day and blurted out, “Last one to finish is a nigger baby.” His mother and siblings recoiled in shock. “We had a black lady cleaning the house. That was my first awareness of differences.” He broke into tears.

“It hurts,” Morrison-Reed responded.

Misunderstanding, Lyon choked out, “I’m sorry.”

“No, it hurts, for you,” Morrison-Reed insisted. “Every child goes through that.”

Talking about race, and about the racism embedded in our culture, is tough. We Unitarian Universalists beat ourselves up over it too much, Morrison-Reed says. He is in a good position to judge. Ordained in 1979, he became only the eighteenth black person to receive ministerial fellowship in the history of the UUA or its predecessor denominations; he was also only the second Afro-American raised in Unitarian Universalism to become a UU minister. Morrison-Reed came of age at a moment in our nation’s and our denomination’s history that has given him a unique window onto our pain around race. He revisits that era in his new book, In Between: Memoir of an Integration Baby.

Morrison-Reed moves easily among the terms Negro, colored, black, even nigger to reflect a time or a context—which makes talking about race with him easy, too. He prefers the term Afro-American to describe those with roots in American slavery, as opposed to more recent African immigrants.

Now retired from twenty-six years of co-ministry with his wife, the Rev. Donna Morrison-Reed, the Rev. Mark Morrison-Reed, 59, spends his time researching, writing, teaching, and guest preaching—largely about Afro-Americans in “the movement,” as he calls Unitarian Universalism, the faith he grew up in. On his weekend gigs, Morrison-Reed meets with a church’s history buffs, preaches on Sunday, then reads from and signs his books.

His Black Pioneers in a White Denomination, first published in 1980, brought to light stories of Afro-Americans among our clergy that had been largely forgotten. At the time, many UUs were in despair about black-white relations. The stories helped get a stalled denominational dialogue going again. And change has come, slowly. In recent years, the numbers of people of color entering UU ministry, though still small, has increased markedly. Stories of reconciliation in our churches are coming forward.

His new memoir, In Between, tells the story of being raised as one of a few Afro-Americans in the two most important institutions of his childhood, church and school. Focusing on his lifelong “spiritual quest for integration,” more than his career in parish ministry, he writes openly about his struggle to find his calling as his world came apart in the “either-or era of Black Power.”

Morrison-Reed has been a pioneer in his own right: as a reconciler. Finding his voice as a minister, he uses story and an open heart to help find integration in our communities, in our denomination, and within ourselves. “Integration is inevitable,” he writes. “There is no other way. Never was and never will be.”

Mark Reed grew up in a middle-class black neighborhood of bungalows on Chicago’s South Side, the son of a nuclear chemist and a social worker. The only time he left it was to attend the First Unitarian Society in Hyde Park.

In 1948, First Unitarian passed a resolution “to invite our friends of other races and colors,” overturning a bylaw prohibiting membership to Negroes and creating a storm of controversy. The Rev. Leslie Pennington threatened to resign if it didn’t pass, and some board members left when it did. In 1954 the Reed siblings were the first Negro children dedicated at First Unitarian, whose membership today is one-third people of color. Over time Mark came to feel more comfortable there than he did in his own black community, spending more time at church—in youth group, singing in the choir, teaching the younger children, later working part-time—than he did at home.

“I grew up in the movement,” he says. “This was home. Growing up in UU culture as a person of color has its challenges, but it is not a big deal.”

Unitarian Universalists have actually done a pretty good job—not perfect, but not bad, either—navigating the minefield of race and culture, Morrison-Reed says. We can take pride in our leadership in the abolitionist and civil rights movements; our General Assembly has made a formal commitment to antiracism and multiculturalism; we’ve elected an Afro-American as the current UUA president. Still, there’s lingering shame that our congregations and leaders are still 97.5 percent Euro-American.

“The issue is increasingly one of class and not race,” Morrison-Reed argues. Religions are always bound to culture and class, and Unitarian Universalism has been shaped by its upper-middle-class, liberal, North American values. The reason we don’t have many Afro-Americans is the same reason we don’t have many working-class or poor members. “Look at the average UU education level, 17.2 years, which is almost a master’s degree,” he says. “There are simply not that many Afro-Americans in that demographic.” But, he predicts, as the number of highly educated and middle-class people of color increases in the general population at large, more will be drawn to Unitarian Universalism, as long as we are welcoming to them.

When Mark Reed was a teen, his father got a physics appointment at the University of Bern, and he attended the Swiss Ecole d’Humanité, a multicultural boarding school. As at First Unitarian, he was one of the only Negroes. Those two institutions, he writes, formed his “most fundamental beliefs: that . . . we are first and foremost human, sisters and brothers belonging to one human family.” But throughout his life, the way the world reacted to him as a black man led him to conclude the combination of white fear and black rage make prejudice inevitable in our culture.

Unlike most blacks in pre-civil-rights America, Reed had never experienced poverty or discrimination, until he went to Switzerland, when the parents of a U.S. embassy child forbade her to go to the movies with him. Then on April 4, 1968, the day the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated, “all middle ground vanished, and an unbreachable wall of hostility went up between blacks and whites,” he writes in his memoir. Young Mark Reed’s integrated world became very uncomfortable, even dangerous.

A few months later, he slipped into a meeting of the Black Student Union at Beloit University, largely out of fear of what would happen if he didn’t show up. In the middle of a speech, the burly football captain came toward him and picked him off the ground by his shirt. Morrison-Reed recalls his words: “First we gotta take care of business . . . Root out those vanilla lovers . . . ’Cuz we got some Uncle Toms right here . . . Got some Oreos . . . Black on the outside but white on the inside . . . We got some niggers with processed minds . . . And Reed here is one of ’em.”

His fellow black students shunned him, and he was too afraid to be seen confiding in white friends. He has spent his adult life sorting out the complex of fear, pain, guilt, shame, and anger that have come with being an “integration baby.” Fear of being beaten up, pain at rejection, guilt at not doing enough for his community, shame at not standing up for who he was, and anger at the injustice of the world.

His memoir is brutally honest about his years of youthful floundering—being kicked out of college twice, dropping out and never graduating, getting fired from a teaching job at his beloved Swiss school for a relationship with a student, escaping with alcohol and comic books.

Constantly aware of having so much when others had so little, he felt a call to give back. Sunday mornings at First Unitarian, especially teaching kindergarten, were among the brightest spots in his week, and he kept returning to the idea of ministry. In 1973 he asked for a meeting with the renowned Afro-American minister, the Rev. Howard Thurman, who told him, “If there is some other way you can do what you want with your life without entering the ministry, you should do it.” There wasn’t, he found. He applied and was accepted at Meadville Lombard Theological School in Chicago, even without a college degree.

The only Afro-American in his class, he went up one day in the student lounge to the only woman, Donna Morrison, an Anglo-Canadian, and asked, “Would you like to teach Sunday school with me?” That collaboration turned to friendship, then love. The couple has led two largely white congregations in Rochester, New York, and Toronto and raised two blond multiracial children of dual nationality.

Their union was another branch in an already multiracial family tree: Morrison-Reed’s mother traced her lineage back to the seventeenth-century marriage of an English trader and a black duchess of Sierra Leone, who herself had some Portuguese ancestry. On his father’s side, two great-grandfathers were white—one the nephew of a plantation owner, and one who lived his life as spouse to a “free Negro” woman he loved but was forbidden to marry under Virginia law, and father to their six children. His forbears were both slaves and slave owners. “Without realizing it, I was being true to my lineage—four hundred years of interracial relations and miscegenation,” observes Morrison-Reed.

Black Pioneers started as Morrison-Reed’s thesis when he was at Meadville Lombard in the 1970s. It’s since gone through three printings, and he’s never stopped researching. What he’s found is a rich history, dating to the late 1800s, of Afro-Americans who pursued liberal religion more or less on their own.

For a century, Morrison-Reed discovered, Unitarians consistently pushed away talented people because no one could imagine a black minister leading a white church or the Association funding a new black church. “We had so little vision,” he comments, “and were so bound up in our own arrogance and our own racism. And we had so little missionary effort. It was not any one of those, but all of them together. We couldn’t really evaluate these men or see their possibilities. If we had, it would have changed the whole texture of Afro-Americans in the movement today.”

Universalists, on the other hand, appealed more to the working class and did more outreach in areas where blacks lived. From 1889 to 1929, for example, a series of black Universalists led successful churches and schools in Norfolk and Suffolk, Virginia. But Universalism, which Morrison-Reed leans toward, had a theological problem in appealing to people who had known slavery: “How do you explain black suffering?” he asks. “To say black and white folks will all be saved in the end will not wash. How come the slave master can do anything he wants to me, sell me, sell my children, and go to heaven, too? That can’t be. He’s got to suffer.”

Black Pioneers was published following a troubled time in the denomination’s own race relations. In 1969 the UUA discovered it was essentially broke and reduced funds it had committed to black empowerment initiatives. Outraged, several hundred delegates—including most of those who were black—walked out of General Assembly. The funds later were cut entirely, and an estimated 1,000 Afro-Americans, including a young William Sinkford, left the UUA in the aftermath.

In the 1970s, leaders encouraged Morrison-Reed to publish his thesis. Reactions to the book were sobering. The Rev. Sharon Dittmar gave a sermon in 1998 about black pioneers in Cincinnati, declaring that, while she loved the faith that believed in the inherent dignity and worth of every person, she was ashamed when she read Morrison-Reed’s history. Her sermon provoked the Cincinnati congregations to explore their history and to reconcile with the descendants of a black Unitarian minister, the Rev. W.H.G. Carter, who had been shunned by their churches in the early 1900s.

Today Morrison-Reed invites us to look at both our history and our still-small Afro-American numbers through a different lens. “Afro-Americans have always been in the movement, many more than we can know,” he says. “In terms of values and achievement and education, they looked just like other UUs. They were all educated—lecturers, inventors, teachers. They were well respected within their congregations. But they didn’t know about each other.”

We need to take a longer view, he says. From the late 1800s through the 1940s, Unitarians and Universalists each had one to two black ministers at any given time. Starting in the 1940s, that number doubled about every fifteen years. By 1970, there were eight; by 1990, eighteen. Today there are forty people of color in parish ministry, sixteen in community ministry or UUA staff, and forty-three seminarians of color preparing for UU ministry.

Other factors are largely outside our control:

Only Southern Baptists are more conservative than the traditional Afro-American churches, which claim more than 80 percent of black churchgoers. “We couldn’t drag many Afro-Americans through our doors if we tried because many of them would disagree with us on central issues of belief,” he writes.

Afro-American professionals who may be attracted to our liberal theology often work in a mostly white world, he observes. So they’re likely to look for a church that is culturally comfortable, one that uses black metaphor, images, language, and music, where they can give back to their community, even if it’s more conservative than their own beliefs.

Starting new congregations is always hard, and success often depends on personality. “If someone is as good as a Howard Thurman, it makes sense to maintain one’s independence. We never give a lot of money, and being associated with us is not necessarily positive, but one more thing you have to explain.”

The UUA has made a serious commitment to increasing diversity and eliminating racism. In 1997, General Assembly delegates approved a resolution calling for “comprehensive institutionalization of antiracism and multiculturalism.” Since then an evolving set of programs has sought to help the denomination make that transformation. In the past few years, the Association has launched a Diversity in Ministry initiative to help congregations and ministers of color through the settlement process.

But Morrison-Reed offers this critique: “The primary driving force is not what we’re doing, not our intention or programs, but demographics. If we do nothing—and I’m not advocating that—things are still going to change. We have to ask not ‘How?’ as much as ‘Why do we want it, and will we be ready for that change when it comes?’”

And that is what he calls “the perversity of diversity.” Integration is not about assimilation, but melding different parts to form a new whole. “Pursue diversity and you invite change,” he writes. “Change and you become something different from what you were drawn to in the beginning. And that is the conundrum.”

Empathy came naturally to Morrison-Reed on that day in Kansas City, when Don Lyon expressed his shame about saying the word “nigger” as a young child. In his memoir, he recalls an almost identical incident from his own childhood. One day he dashed in from playing with a friend to tell his mom the poem he’d just learned: “Look in my eye. What do you see? A little black nigger / Trying to hypnotize me.” Horrified, she demanded to know who had taught him that. He was not to play with that boy again. “I won’t have you talking like poor white trash. We’re not common Negroes.”

Our childhood experiences are key to untangling our confusion and reactivity about race, he believes. For Morrison-Reed, the challenge was reconciling his mother’s powerful insistence on courtesy and learning “the secrets of surviving in a white world” with the black power movement’s belief that interracial solidarity was a trap that debased blacks and with finding his own place in the world—black, white, and integrated.

“I don’t believe in original sin,” he says, “and I don’t believe people are born racists. It’s a virus we catch because it’s part of the fabric of the culture.”

In 1982 he was helping run the junior camp at Ferry Beach. The staff learned that a camper had said something hurtful to the one Afro-American camper. The six leaders were ready to come down hard, but he persuaded them to take a different tack.

“The first thing we need to admit about racism is that none of us wants to be racist,” he says. “We have to have a handle on our own goodness before you can do that work: You knew better. It’s not the way you want to be. You’re still a good person.”

So Morrison-Reed led the group in an exercise, which he has repeated many times since. First he asked the kids to share a time they felt loved and lovable, then when they first saw prejudice, then when they saw it and didn’t say anything, then when they participated in it.

“I’m 100 percent sure that when children see prejudice, they know that’s not fair. Most children will protest or question the first time, and often they get slammed. The next time they don’t speak up, and eventually they may even join in. That gave them the experience of seeing how it gets layered in.”

At a Sunday service at All Souls in Kansas City last December, Morrison-Reed approached the pulpit dressed in a rich maroon collarless shirt, a blue suit, black Mephisto sneakers, his dreads pulled back in a black scarf. He took a long pause, then spun out a story the way Garrison Keillor might have, if he’d grown up spending holidays at a tall, narrow, brick row house in Washington, D.C.

Morrison-Reed’s deep voice caressed the descriptions enfolded in his memory: a huge crystal chandelier orbiting over his great-aunt’s dining table, the glossy red steps, his great-uncle’s mystery-filled basement kingdom. As he whispered breathily into the microphone, you could taste the litany of foods: “corn pudding, tangy greens, Smithfield ham, mashed sweet potato covered with melted marshmallows, rich brown gravy.” He even read the entire recipe he’d found in a diary for “Mama’s Christmas Plum Pudding,” a concoction of suet and dried fruit boiled for five hours.

Toward the end of his talk, he pulled out a tissue, overcome with “memories of what was and can never be again.” Throughout the sanctuary came the sounds of sniffling, tissues rustling, and the wiping of tears and noses.

Though his story was woven with his family’s traditions and culture, race had nothing to do with his listeners’ reactions to his tale of loss and love. How much we all have in common, how parallel our stories—new couples torn between two families, bittersweet milestones that mark the passing of time and of loved ones, the joy of reuniting and doing again what we’ve always done together—was obvious.

Stories are so powerful, Morrison-Reed says. This is something we can learn from the traditionally black churches, and from people of color as they come into our faith.

The fundamental issue is not race, he charges, but that we UUs are afraid of the spirit, and we get lost in our heads. “If God gets his hands on us—or if Guadalupe gets her hands on us,” he says, referring to Mexico’s patron saint—“we might do something crazy. We are scared to death of that, and are dying to have that experience at the same time.

“What our movement needs shouldn’t focus so much on race,” he continues. “It should be: What do we need to become more open to the spirit and more accessible in general—in our music, liturgy, celebration, and story? What is it we’re inviting people to? What would it take to have more uplifting services, where people didn’t care if it ran over an hour, and weeping was part of it? That will speak to all of us more deeply. And we would have more success drawing people in across the board.”

See sidebar for links to related resources.