UU scientist battles arsenic-poisoned water in Bangladesh

Vermont chemist Seth Frisbie calls tainted wells the “largest human poisoning in history.”

Dr. Seth Frisbie, a chemistry professor at Norwich University in Northfield, Vt., and a member of First Church in Barre, Universalist, in Barre, Vt., is dealing with such a problem.

Frisbie, 54, with a Ph.D. in environmental chemistry, is one of the world’s foremost experts on arsenic. In 1997 he was working on ways to clean arsenic from Superfund sites in this country when he was invited by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to take on a bigger problem. Thousands of people were getting sick in Bangladesh from arsenic in the drinking water.

Traditionally, Bangladeshis have drunk surface water from streams, rivers, and ponds. But starting in the 1970s, widespread bacterial contamination became a problem, and people were coming down with diarrhea and cholera, common causes of death in developing countries. So around 10 million wells were drilled to tap into clean underground water for drinking. In a generation, more than 95 percent of Bangladeshis went from drinking surface water to drinking well water.

But then, after the country was converted to these “tube wells,” it was discovered that arsenic was widespread in this system of wells. That’s when Frisbie was summoned.

He and other researchers made a national survey of arsenic-affected water wells. Frisbie discovered that many of the wells also contained other harmful metals—manganese, uranium, lead, nickel, and chromium. All these metals, including the arsenic, were naturally occurring in this part of the world.

And they were making people sick. People were showing up by the thousands with skin and internal cancers, gangrene, miscarriages, Parkinson’s-like symptoms, and organ failure.

When Frisbie made the connection between the rash of illness and the metals in the water, he tried to explain it to the government of Bangladesh, to USAID, and to the World Bank, but there was little understanding or willingness to comprehend, he said. Then he found someone who did understand the problem—Dr. Bibudhendra Sarkar of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Frisbie, his wife Erika Mitchell, and Sarkar assembled a team of scientists who, paying to do their own research, were able to conclude that more than 50 million Bangladeshis were drinking a toxic soup that would, over a span of years, harm or kill many of them if the metals were not neutralized. The situation was—and is—“the largest human poisoning in history,” said Frisbie.

Frisbie very quickly gets emotional talking about the discovery of the full extent of the range of metals in the water. “There was a point when I was the only person in the world who knew that tens of millions of people were drinking water with at least one other toxic metal in it besides arsenic. And that it was making them sick. I tried to make others understand it and no one really got it. It was hell on earth to know that and not have others understand it.”

For most of the 16 years Frisbie has worked on drinking water quality and public health in Bangladesh he has paid for his research himself. USAID paid for his first month on the ground and not much more. He estimates he has spent well over $100,000 of his own funds. In one critical phase of his work his wife took a teaching job in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, to support him while he was in Bangladesh. At another point she became extremely ill while working at the cholera hospital in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.

Frisbie has done much of his Bangladesh research through Better Life Laboratories, which he founded in 1997. He developed an inexpensive and highly sensitive laboratory method for measuring arsenic in drinking water. There is no other way to measure arsenic to such low concentrations with the equipment that is commonly available in Bangladesh. As a result, this method can save thousands of lives by allowing people to identify and use the safest drinking water wells in affected neighborhoods. He also helped develop a pilot water treatment plan for arsenic removal, but it is only available in a limited way.

Frisbie helped develop some other partial solutions. Wells that were contaminated with arsenic and metals were identified and people were asked to share the good wells. And about 30 percent of the contaminated wells can be made usable if they are drilled deeper. That work is underway.

To solve the water problem completely would require installation of municipal-type water systems, with centrally treated water that is delivered in pipes to the surrounding homes and businesses. But in a country as poor as Bangladesh, that’s not going to happen any time soon, says Frisbie. His goal now is to educate young scientists who can carry on this work. And he will continue plugging away at possible solutions.

UU support

Religion helps Frisbie stay engaged with this overwhelming challenge. Raised Baptist, Frisbie said he remains a Christian. In 1992, no longer able to believe that a loving God would damn people who were not Christian, or to believe that God favored one religion over another, he began attending First Parish in Framingham, Mass. “I believe God is too big to be contained in just one religion,” he said. Later he migrated to the Unitarian Church of Montpelier, Vt. Almost two years ago he began attending First Church in Barre, Universalist.

At Barre, he is a member of a covenant group. “I’m getting a phenomenal amount of support from our minister, the members of this covenant group, and the congregation,” he said. He is writing a sermon called “A Scientist’s Beliefs.” In it he describes his belief in God as described in the Gnostic Gospels and how God is present in every person. “There is a divine goodness in each and every person, but it is up to the individual to cultivate this goodness,” Frisbie said. “In addition, this goodness is not only inside each of us, it’s all around us as well. This goodness is in the beauty of nature, the kindness of a stranger, the smile of a friend, and the touch of a loved one.”

God as goodness drives his work, he says. “Each of us has a responsibility to use the gifts that God has given us to spread goodness, kindness, and love,” said Frisbie. “As I look back on my life I now realize that I was guided through every major decision and given every major opportunity by being aware of and acting on this goodness.”

He added, “All of this let my research team help solve the largest mass poisoning in history and improve the lives of tens of millions of people in Bangladesh.”

The Rev. Dr. M’ellen Kennedy, minister at First Church in Barre, added, “What strikes me is that Seth could make a lot of money doing other things, but he chooses to do this work because he cares so deeply. He’s using his gifts to help others.” She and Frisbie presented a water service about his work a year ago. He has also spoken to other congregations about his work.

UUs or congregations that want to help can make contributions to Frisbie’s Better Life Laboratories, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization. Contributions will go toward scientific research in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

There is a bright side to this work. Even though Bangladeshis continue to sicken and die from bad water, millions of others are now drinking good water. And with some work, millions more can get to that point.

“I have no choice but to keep working on this,” said Frisbie. “As long as I have the ability to prevent human suffering on such a massive scale I have no choice. Still, it’s been very hard. I do feel a responsibility to continue with this work. If I don’t, people will get sick and die.”

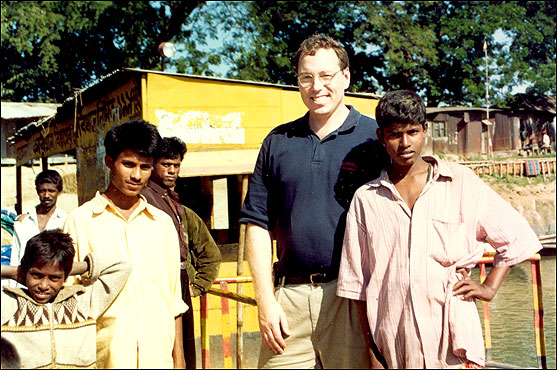

Dr. Seth Frisbie (center) travels frequently from Vermont to Bangladesh to measure arsenic levels in drinking water and help people identify the safest wells to use. See sidebar for links to related resources.

Comments powered by Disqus